Wednesday, March 2nd, 2011

Caillebotte and Hopper

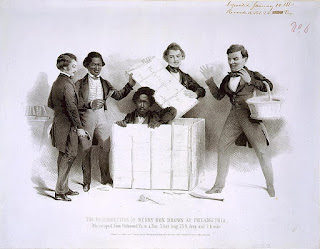

Today a perceptive student asked if art historians had ever discussed a connection between the paintings by Gustave Caillebotte (a 19th century Impressionist) and Edward Hopper (a 20th century artist). I thought this was a really fascinating question. This week, my students and I have been discussing how Caillebotte’s work can be interpreted within the themes of isolation and loneliness. We’ve discussed ideas of how the modernization and industrialization of Paris could have isolated people in the 19th century, and particularly analyzed Caillebotte’s painting Pont de l’Europe (1876, see right). My students and I looked at Caillebotte’s biography, using some of the research done by my friend and colleague Breanne Gilroy. One thing Gilroy mentions is that Caillebotte experienced a sense of isolation during his lifetime, particularly since the artist’s father, brother, and mother all died within a period of four years.1

Anyhow, I thought that my student’s question regarding Edward Hopper was especially interesting in this context, since Hopper’s paintings also can tie into themes of isolation and loneliness. One can especially get a sense of isolation in Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942) and Gas Station (1940). Caillebotte and Hopper are also similar in other ways as well: they both have an interest in depicting contemporary subject matter, both use comparatively muted color palates, and both favor compositions with large, flat areas of color.

Although I didn’t find too many people who discuss a similarity between the two artists, I did come across a few things. First of all, Time blogger Richard Lacayo noted that he saw a similarity between the compositions of Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877) and Hopper’s New York Movie (1939). Lacayo also noted a essay by Judith A. Barter in the catalog Edward Hopper.

Although I haven’t seen a copy of Barter’s essay, this evening I was able to listen to a podcast in which Barter discusses more of Hopper’s life. Barter mentions that Hopper went to France three times between the years 1906-1910. While there, Hopper viewed and studied the art of many Impressionist painters, and I think it’s very likely that Hopper was familiar with the work of Caillebotte. Although Baxter doesn’t cite Caillebotte as a direct influence, she does mention a similarity between Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day and Hopper’s Nighthawks (side note: it isn’t surprising that she chose these two paintings for comparison, since they are both part of the Art Institute of Chicago collection – the museum where Baxter works as a curator!). Here is a transcript from the podcast:

“Hopper’s…viewer witnesses the street corner and figures in Nighthawks in much the same way that Gustave Caillebotte saw the boulevard section in Paris Street, Rainy Day…But there is an important difference: unlike Caillebotte’s pedestrian, who is part of the moving traffic of the street, Hopper’s observers are further distanced and stand outside the vision of the figures that the artist paints. Hopper eliminates all pedestrians, removing the observer from the observed. This is the core of his city subjects: the experience of watching unobserved.”2

1 Breanne Gilroy, “Mourning and Melancholy in the Work of Gustave Caillebotte,” (Unpublished), 2006. Gilroy mentions how Caillebotte’s father died in 1874, his brother René died in 1876, and his mother died in 1878. Gilroy also cites an article by Kirk Vardenoe, “Gustave Caillebotte in Context” in Arts Magazine 9 (May 1976): 94-99.

2 Judith A. Baxter, “Transcending Reality: Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks,” public lecture delivered 28 February 2010. Podcast of lecture is available here.