Wednesday, February 28th, 2018

Observing Flowers: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites

Jan Van Eyck, “Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Oil on panel, 2′ 8″ x 2′ 0″. National Gallery of Art (London)

I am really sad that I am unable to see the exhibition Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites that is going on at the National Gallery in London right now (until April 2, 2018). This show has some of my favorite artists and works of art, including Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, which is one of the first works of art that I came to love as a teenage student. I also love thematic exhibitions that link works of art by their content (such as symbols and subject matter): this exhibition revolves around the inclusion of the convex mirror in both Van Eyck’s and the Pre-Raphalites’ art. What a fun and novel idea for a show! Even though I can’t travel to England for this exhibition, I look forward to reading the catalog.

The basic premise of the show explores how the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was inspired by the art of Jan Van Eyck. The Arnolfini Portrait was acquired by the National Gallery in 1842. Just six years later, in 1848, the Pre-Raphalite Brotherhood formed. Despite their name and connection to an Italian artist (Raphael), this group of artists were not very familiar with Italian art. Instead, they looked to early artistic examples that were available to them, such as medieval art or the including the newly-acquired painting by Van Eyck. As an Early Northern Renaissance painter, Van Eyck embodied art that was anti-classical or un-classical, which is what the Brotherhood strove to depict in their art. Furthermore, the Pre-Raphaelites were inspired by the rich colors and extreme detail for which Van Eyck was famous, even during his own lifetime. I love this video that the National Gallery created to promote the exhibition:

I think this connection to Van Eyck is a really great way for students to understand how the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood style is unique and different from the other art produced in Britain in the 19th century, not only in terms of subject matter but also style. Van Eyck’s art is highly detailed and has very bright, saturated colors; such features are also a hallmark of Pre-Raphaelite art. As a Northern artist, Van Eyck was influenced by the Aristotelian mindset that places value on finding knowledge through empirical observation. This parallels with how the Pre-Raphaelites, as influenced by the art critic John Ruskin, sought to depict truth and find a moral, virtuous foundation by studying nature. All of these artists were compelled to look closely at the world around them.

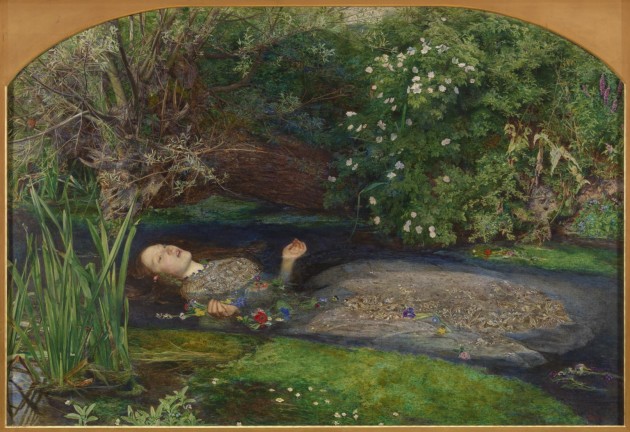

As a gardener, I especially like to think about how Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites are similar in how they studied the natural world through plants and flowers. One of my favorite Pre-Raphaelite paintings is Millais’ Ophelia (1851-52), and a Smarthistory video includes amusing anecdotes about the practical frustrations that Millais experienced by going into nature to paint this scene.

This painting has a lot of very specific flowers included therein, which are part of the Shakespearean story of Ophelia from the play “Hamlet.” Millais took special pains to make sure that all of the plants were identifiable, especially since they each held symbolic value. Millais even furthered the floral motif by depicting his model in an embroidered floral dress which he bought specifically for inclusion in the painting.

The Rag Rose blogger, a fabric florist named Ruth, has identified the different plants and flowers found in this painting. One of my favorite flowers in the painting is the poppy (a symbol of sleep and therefore death), placed in the water near Ophelia’s hand. I also like the small pansy laying on her dress, since Ophelia says in the play that pansies represent thoughts:

Like Millais, Van Eyck also paid strict attention to detail when he painted his flowers, which emphasizes that he keenly looked toward nature when painting. Although flowers aren’t depicted in the Arnolfini Portrait, there are other identifiable flowers included in another famous work of art by Jan Van Eyck and his brother Hubert Van Eyck: the Ghent Altarpiece. In fact, Van Eycks’ attention to botanical detail is so striking that a few years ago an exhibition was dedicated to the plants shown in the Ghent Altarpiece. Here are two details of some of my favorite flowers in this painting, including lilies, irises, roses and columbine:

Jan and Hubert Van Eyck, the Ghent altarpiece (“Adoration of the Mystic Lamb”), 1432. Detail of the Virgin’s crown

As with Millais, Van Eyck included flowers for symbolic purposes, and many of them relate to the Virgin. For example, white lilies are associated with the Virgin because they are a symbol of purity. Roses are associated with the Virgin: her virginity was compared to an enclosed garden and she was known as by titles such as the Mystical Rose.

Although these artists were separated by about 400 years, there are some definite similarities in their art. Millais and Van Eyck had a love for depicting fine details, a similar interest in using symbols to depict literary or biblical themes, and a devotion to accurately depicting nature. If anything, I think that Millais had an easier time depicting nature than Van Eyck, since the recent invention of oil paint in tubes enabled Millais to go outdoors to paint. As I myself sit indoors and impatiently wait for spring to begin, I especially love these vibrant, detailed paintings because they help keep flowers alive for me all year long.

I saw the exhibition some months ago. Van Eyck is a particular favourite of mine and I’ve seen the Arnolfini Portrait many times at the National Gallery. For me, he is a pivotal figure in European Art. I’m interested in the PreRaphaelites and I was keen to see this. For me, though, the exhibition delivered little of what it promised.

I was expecting an examination of Van Eyck’s influence on the PRB. Here it is reduced to following the trail of mirrors and reflections. It’s an interesting premise, as you say, but it’s not enough to hang an exhibition on, not here anyway, and there’s an awful lot of padding out.

The PRB paintings are an arbitrary selection, I’d describe the best of them as fine paintings rather than “great works”, and others are there because they feature mirrors. Ophelia for example is not included, although Mariana is. And then there is an entire room devoted to artists, who were not members of the PRB, but who painted mirrors. This includes a partial copy, by an obscure Victorian artist, of Las Meninas, to make the point that Van Eyck also influenced Velázquez, who would have known the Arnolfini in the Spanish royal collection. It also includes William Orpen and Mark Gertler who are much much later. It’s quite bizarre.

At the centre of this mishmash was the only masterpiece in the whole thing, the Arnolfini Portrait itself. And once you’d seen it, the other works just faded away. There is the makings of an interesting exhibition here if they had looked at how the early paintings then in the National Gallery influenced the PRB. Maybe that will be in the catalogue.

I enjoyed your blog post more.

I am interested in how the show explores the link from the art of Jan Van Eyck to the art of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood ages later. Yes the vibrant PRB paintings help keep nature beautifully alive for the viewer, but lots of other artists loved that concept.

Hi Anne! Thank you so much for your thoughtful comment. Now I don’t feel quite as sad at missing the show, knowing that you found it a bit bizarre and confusing. It sounds like the focus on mirrors as a theme got a little bit too out of hand, especially if the exhibition included a copy of Las Meninas and other paintings of non-PRB artists who painted mirrors. It sounds like I’ll get sufficient experience and information by just looking at the catalog.

And I think most works of art fade away if they are placed in comparison with the Arnolfini Portrait. I think that painting and the Ghent altarpiece are two of the most significant and impressive paintings in Western art!

Hi Hels! Yes thank you for your comment. There are definitely other artists who also loved to keep “nature beautifully alive.” I actually thought of several Dutch still-life artists and their painted flowers as I was writing this post. I also thought of my experience volunteering at my local museum about a year ago; I led tours on an exhibition titled “Seeing Nature,” which showvased paintings from the 17th to the 21st centuries. There are so many ways that artists have kept nature alive in art, and a strict attention to floral specimens is just one way.

Ophelia is my favorite.