Thursday, May 18th, 2017

Etruscan Terracotta Sculptures and Vent Holes

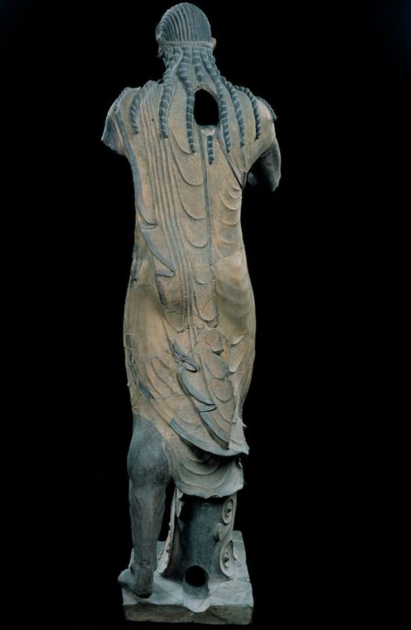

I’ve been thinking about the statues from the Temple of Menerva (also spelled Menrva) at the ancient Etruscan city of Veii this week. Tonight I found a cool image that shows the back of the “Apollo” statue. This image shows two intentional holes that created so that the terracotta would be properly ventilated during the firing process.1 One hole appears just about where the shoulder blades should be, and another is seen at the base of the decorative support between Apollo’s legs.

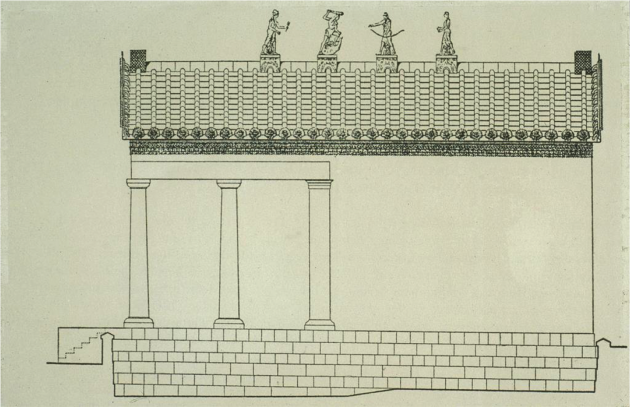

Drawing of the Temple at Veii with four specific figures (from L-R): Turms (Mercury), Hercle (Hercules), Aplu (Apollo) and Letun (Diana) on the ridgepole of the roof

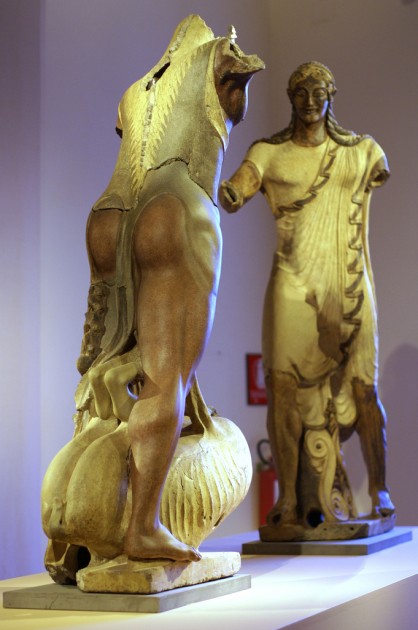

The Apollo sculpture comes from a group of four figures that would have decorated the ridgepole of the Temple of Minerva at Veii (although many other figures would have also been included along the roof of the temple, as shown in a reconstruction model). This group of figures would have referenced the third labor of Hercules, in which he is sent to capture the sacred deer with the golden horns: the Golden Hind. This deer is sacred to Diana (Apollo’s sister), and Apollo is struggling with Hercules over the deer. For more of the story, see the Smarthistory video and article on the topic.

The figure of Diana has been ruined and lost over time, and today only the head of Mercury and a little bit of the body remain. However, a good portion of the Hercules figure exists today, although it is not in as good of condition as the Apollo.2 A back view of the Hercules sculpture reveals that it has similar vent holes (between the shoulders and at the bottom of the sculpture). I assume that the holes in the deer’s body are were created for ventilation purposes.

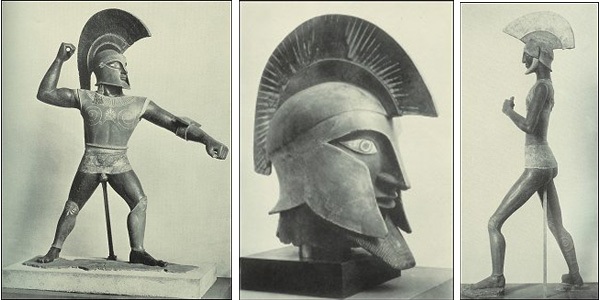

Despite that terracotta doesn’t preserve extremely well, I’m glad that we have enough authentic Etruscan terracotta pieces to enjoy today (complete with authentic ventilation holes) to help us know more about the Etruscan people. Although a venting hole may seem like an insignificant technical detail, it actually can help us identify authentic works of art. For example, the Etruscans’ use of ventilation holes helped to identify later forgeries that were created in the Etruscan style. In the early part of the 20th century, three such forgeries were created by Alfredo Fioravanti and Riccardo Riccardi (with the exception of the Colossal Warrior, which was made with the help of some of Riccardo’s family members after Riccardo’s death). These forgeries were of terracotta warriors; they were acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and displayed together for the first time in 1933.

The Colossal or Heroic warrior (left), Colossal Head (center) and “Old” Warrior (right), c. 1915. The Colossal warrior is approximately 8 feet tall (about 243 cm), The Colossal Head is 4.5 feet (137 cm), the “Old warrior is 6.6 feet (202 cm).

But in 1961, the Met had to admit that they had purchased works of art that were fakes. One of the tell-tale signs that these warriors were not Etruscan has to do with the vents: each warrior only had one vent, unlike the Etruscan works of art that are fired as a single unit with multiple vents (as shown in the Apollo and Hercules sculptures).3 This indicates that the large forgeries were fired separately and then reassembled. The modern day forgers did not have a kiln large enough to fire these large-scale objects! If they had taken the time to build such a kiln (and in turn create the proper number of ventilation holes), I wonder if it would have taken experts longer to determine that these sculptures were forgeries!

UPDATE: In a lecture I attended by Dr. Richard Daniel De Puma, he explained that the subject matter of male warriors was intentionally picked by the forgers Fioravianti and Riccardi. The forgers knew that John Marshall, the foreign agent for the Metropolitan Museum of Art located in Rome, was gay and thought the subject matter of male warriors would appeal to him. The forgers singled out Marshall, who often dined at the same restaurant, and attracted his attention by speaking loudly about Etruscan art while they dined. Marshall and the forgers became acquainted and the forgers eventually led Marshall to the forgeries, even taking him past an archaeological site first to make the art seem more authentic.

Eventually, scholar Harold Woodbury Parsons set out to show the Marshall had been duped. Ironically, even Parsons’s agenda relates back to homosexuality, since Parsons viewed Marshall as competition and rival (at one point, Parsons had a romantic interest in Marshall’s partner, Edward Perry Warren).

Dr. De Puma explained that he was involved in the recent redisplay of the Etruscan art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He strongly advocated that at least one of the forged terracotta warriors be put back on display, but due to financial and space considerations, the museum decided to put only authentic objects on display instead. Today, these terracotta warriors are in need of restoration, and, understandably, the museum would rather spend money to restore authentic works of art.4

1 Edward Storer, “The Apollo of Veii” in Broom: An International Magazine of the Arts 2, no. 13 (June 1922): 238-239. Storer explains that the figure was fired as a single unit and that the terra-cotta is about an inch and a quarter thick. Article is available online at: http://bluemountain.princeton.edu/bluemtn/cgi-bin/bluemtn?a=d&d=bmtnaap192206-01.2.19&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-#

2 Another well-preserved figure that decorated the roof of the Temple of Veii exists today, although it is separate from this group of four figures that relate to the Golden Hind myth. This additional figure is of Latona (Leto), a goddess with the child Apollo.

3 The fragments of the figures also did not align properly, which also indicated that they had been fired separately. Experts also became concerned when they discovered that the glazes contained chemicals that were not in use during the Etruscan era. For more information see the book “Etruscan Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art” (p. 295-297) as well as the online articles “Tracking the Etruscan Warriors” and “The Case of the Etruscan Warriors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

4 Dr. Richard Daniel De Puma, “Etruscan Forgeries.” Lecture, The Ridgway Lecture 2019-2020 from University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA, September 28, 2019.

I am newer to your art history blog. I am enjoying your personal reactions to the works and insights. I teach Art History survey courses and am pleased to see the image of Apollo from behind. The Etruscans created dynamic figures, you can sense movement in the drapery. Thank you!