Saturday, April 30th, 2016

Abu Simbel, Dendur, and Jackie Kennedy

Earlier this month, I explored with my students how new meanings and associations with the Temple of Rameses II have been created in recent decades, largely due to the removal of this temple from its original site. In the 1960s, this ancient Egyptian temple fell under threat due to the creation of the Aswan High Dam. Engineers knew that the dam’s resulting reservoir (which is called Lake Nasser today) would submerge this temple under water.

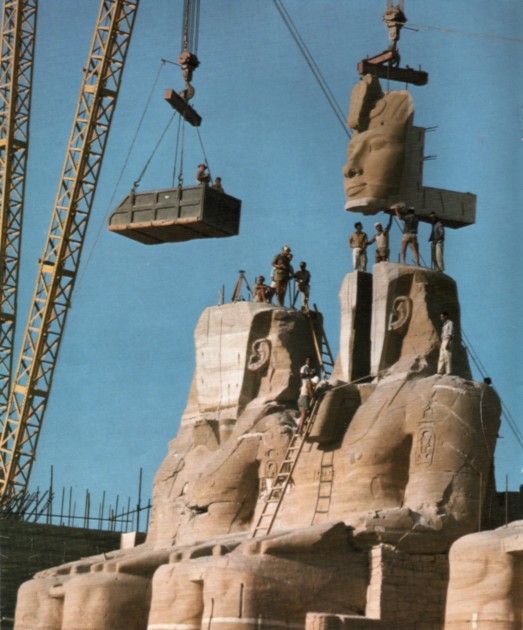

Teams from across the world came together to help figure out a way to preserve the Temple of Rameses II and its neighboring site, the Temple of Hathor. The different proposals and projects are covered well in a “Monster Moves” documentary. Ultimately, the proposal made by Egyptian engineers was accepted, and it was decided that the temple would be cut down and transported on land to another site located 65 meters higher and 200 meters away from the water.

Transportation of the Temple of Rameses II colossal statues. Image from Forskning & Framsteg 1967, Issue 3, p. 16. Image courtesy Wikipedia

It was estimated that this project would cost $32 million, with the US, Egypt, and UNESCO splitting the bill evenly. In the end, the project ended up costing more than $40 million altogether. Preparations began to move the structure in 1963, and then the structure was moved between 1964-1968. My students and I discussed how this project ended up being one of international collaboration, which is significant during the 1960s since there were so many political conflicts that were dividing people from one another: the Vietnam War, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

One other political event in the United States that took place during this time was the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Jr. Interestingly, JFK lobbied to help preserve historic sites in Egypt due to the threat of the Aswan High Dam: on April 7, 1961, JFK sent a letter to Congress, recommending that the United States participate in this UNESCO-led campaign. Unfortunately, JFK did not see the completion of the relocation of the Abu Simbel temples. He was assassinated on November 22, 1963, just six days after the contract was signed between the Egyptian government and the firms that were selected to help with the move.

Although JFK didn’t live to see this project completed, his wife Jackie Kennedy did. In fact, it is probably more significant that Jackie lived through the completion of this project: she was a driving force to have American support for the relocation of the Abu Simbel temples, after she was alerted about this campaign by Luther Gulick. She personally wrote to JFK and appealed to him, saying, “It is the major temple of the Nile – 13th century B.C. It would be like letting the Parthenon be flooded. . . . Abu Simbel is the greatest. Nothing will ever be found to equal it.”1 It is Jackie Kennedy’s initial appeal to JFK which ultimately impacted Congress’s decision to support this relocation.

In gratitude for Jackie Kennedy’s role in helping to preserve the Abu Simbel site, the President of Egypt, Gamal Abdel-Nasser, presented Jackie Kennedy with an ivory sculpture of an ancient Egyptian barge. In addition, the President of Egypt wanted to give a gift to the people of the United States, in order to show appreciation for the help given at Abu Simbel. The Temple of Dendur was selected as a gift. Similar to the Abu Simbel sites, this monument also had to be deconstructed and relocated due to the Aswan High Dam. It was offered to the United States in 1965. Jacqueline Kennedy hoped that the Temple of Dendur would be housed in Washington, DC, in order “to remind people that feelings of the spirit are what prevent wars.”2 The Smithsonian in DC even proposed to house the temple on the Potomac River, but this proved problematic for preservation. In fact, many other museums vied for the opportunity to house this structure (which resulted in what journalists called the “Dendur Derby“), but ultimately the Metropolitan Museum of Art was chosen for the temple’s location in 1967.

Temple of Dendur, c. 15 BC. Dendur, Egypt. Located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image courtesy Wikipedia via Jean-Christophe BENOIST

So, now the next time I think of Abu Simbel or visit the Temple of Dendur at the Met, I’m going to think of Jackie Kennedy! The more I learn about Jackie Kennedy and her support of the arts, the more I am impressed with her. For example, she ensured that numerous artists were invited to her husband’s inaugural speech as president, as a way to showcase the Administration’s intentions to support the arts. I think that her involvement with Abu Simbel helps to fulfill this aim of the Administration too, through supporting global art and the preservation of historical art.

1 Caroline Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy (Hachette Books, 2011). Available online HERE.

2 Ibid.