Tuesday, January 13th, 2015

The Status and Social Climate of Ancient Artists

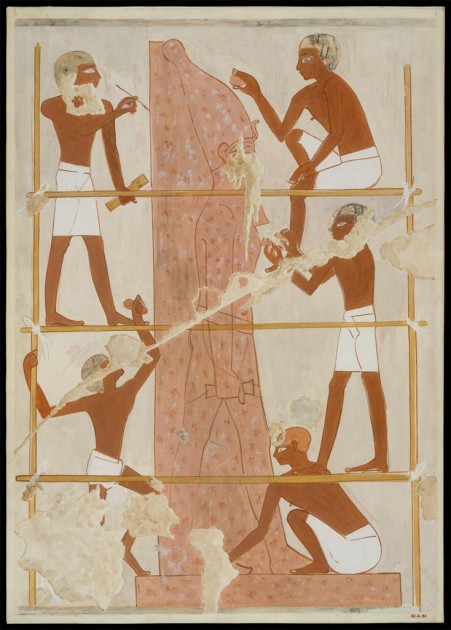

Nina de Garis Davies, 20th century facsimile drawing of “Sculptors at Work,” from the Tomb of Rekhmire, original of ca. 1479-1425 BCE

Right now I am teaching a course that explores what is means to be an artist, in terms of how society defines artists, the societal status of artists, and how artists define themselves. The scope of the class focuses on Renaissance art up until World War Two, but the theme of this class has also made me personally think lately about ancient artists. I thought I would jot down a smattering of things that interest me about the role and societal situation for artists in ancient times. I realize that this post isn’t a comprehensive discussion by any means, and I would love to know other thoughts on this topic in the comments.

Egypt

The word “artist” and its connotations today didn’t exist in ancient times. Instead, in ancient countries like Egypt, artists were thought of more as artisans or craftsman. However, such artisans and craftsmen were still given some status and recognition at times. In the New Kingdom, artisans who decorated and carved the royal tombs were given the designation “servant in the Place of Truth.”

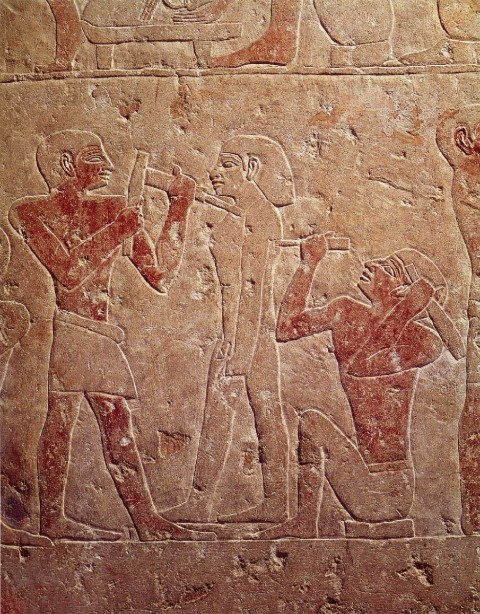

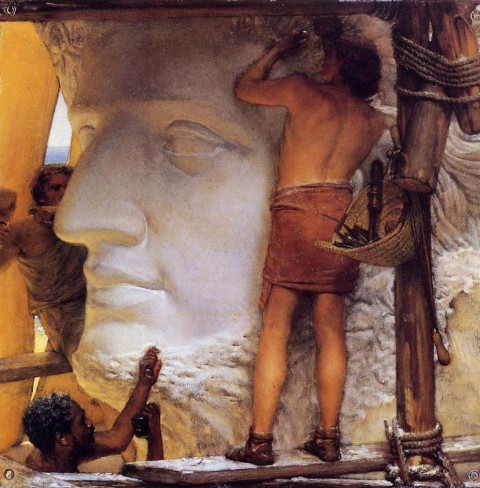

I personally like how there are a lot of artisans that are highlighted in tomb carvings throughout ancient Egyptian history. Some of my favorites include images from the Tomb of Rekhmire, in which sculptors who are working to carve royal statues (see detail at the top of this post) as well as a sphinx (see a full image HERE). Another favorite image is a relief depicting two sculptors working on a statue, from the mastaba of Kaemrehu, Saqqara (see below). In some cases, these images of artisans are included to explain the role of the tomb owner. For example, Rekhmire was a governor whose duties included overseeing the efforts of various craftsmen.

Relief depicting two sculptors carving a statue, from the a, Old Kingdom, c.2325 BC. Painted limestone.

Ancient Near Eastern Art

I recently learned that there were special words in the ancient Near East to designate someone who was skilled in crafts. The Sumerians used the word ummia (meaning “specialist”), and soon after the Akkadians adopted a similar word for craft workers, specialists and artisans: ummanu.1 Similar to the later craft traditions in the medieval and Renaissance eras, ancient near Eastern craftsmen were trained as apprentices. In time, these apprentices could reach the status of a journeyman or a master.2

Interestingly, there were instances in the ancient Near East in which artists were expected to deny that they had any part in the creation of the work. In 1st-millenium texts from Nineveh and Babylon, it is recorded that in the “Washing of the Mouth” ceremony, which endowed certain works of divinely-inspired images with a salmu (a personhood), artists undertook a ritual to swear “their lack of participation in the image’s creation and attributing it instead to the gods.”3

Ancient Greece

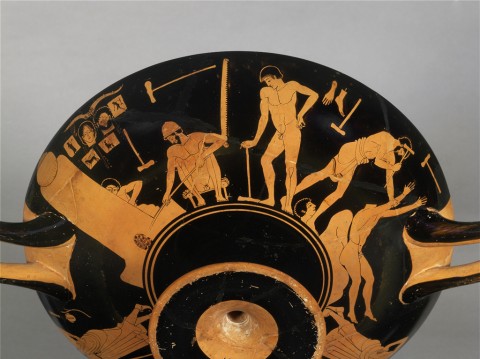

Foundry Painter, “A Bronze Foundry,” 490-480 BCE. Red-figure decoration on a kylix from Vulci, Italy.

For the most part, Greek artists were not held in extremely high regard, which led the Roman philosopher Seneca to write, “One venerates the divine images, one may pray and sacrifice to them, yet one despises the sculptors who made them.”4

However, there were a few artists who were able to establish somewhat of a reputation and achieve renown (I’m particularly thinking of Phidias and Praxiteles). One way that Greek artists vied for status amongst each other was through competitions (such as the competition to create an Amazon warrior for the temple of Artemis).

Ancient Rome

Although Romans loved to copy ancient Greek art, they held somewhat of a similar attitude toward artists as their Greek counterparts. In fact, Roman writers commented that even great Greek sculptors like Phidias could not escape their disdain.5

In the latter part of the Roman Republic, we know that artists banded together to form collegia, which are associations that are similar to the guild system that existed in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Just like this later guild system both helped and hindered the status of medieval and Renaissance artists, collegia also experienced government sanction and restriction.6

Conclusion

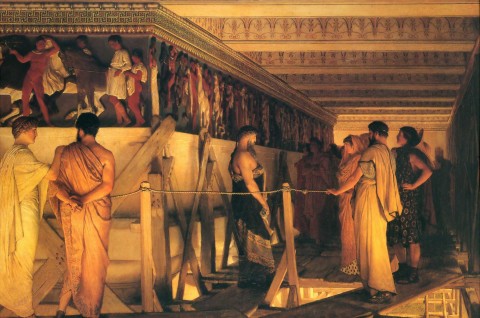

I thought I’d share two of my favorite paintings that are dedicated to ancient artists, although they were created in the 19th century by Lawrence Alma Tadema. I think that these paintings are a little bit more indicative of 19th century taste (particularly in the painting of Phidias, who shows off his Parthenon frieze to his friends as if they are at the opening reception of a gallery), but I still think they are fun.

Lawrence Alma Tadema, Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, 1868. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, “Sculptors in Ancient Rome,” 1877. Private collection, image courtesy of WikiArt

Do you know of other depictions of ancient artists, either from ancient or modern times?

1 Don Nardo, Arts and Literature in Ancient Mesopotamia, (Farmington Hills, MI: Lucent Books, 2009), 12.

2 Ibid., 14.

3 Marian Feldman, “The Lives of Mesopotamian Monuments: Knowledge as Cultural BIography,” in Dialogues in Art History, From Mesopotamian to Modern by Elizabeth Cropper, ed., (New Haven: Yale University Press), 48.

4 Emma Barker, Nick Webb, and Kim Woods, The Changing Status of the Artist (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 12.

5 Ibid.

6 Britannica Encyclopedia, “Guild.” Available online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/248614/guild. Accessed January 11, 2015.

I found a couple of references to Egyptian artist as “outline scribes.”

http://www.louvre.fr/en/expositions/art-outline-drawing-ancient-egypt

https://books.google.com/books?id=JOtxmZ2MaoUC&pg=PA8&lpg=PA8&dq=%22outline+scribes%22&source=bl&ots=fUN3N4fjVa&sig=TkAj0rh_mhimCsvXokNq3Z8o2jM&hl=en&sa=X&ei=MbfjVJaADYGvogSlrIL4DQ&ved=0CCQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22outline%20scribes%22&f=false

Hi Ric! These links are fascinating! Thank you for sharing them with me. I look forward to discussing Egyptian “outline scribes” with my students in the future.