Wednesday, March 26th, 2014

Dali’s “Metamorphosis”: Paranoiac-Critical Activity and the Artist-Genius

I love this photograph of Salvador Dali, because I think that it typifies a lot of ideas regarding Dali’s own persona and his art work. On one hand, the photograph is somewhat similar to a double image (a typical visual trope that appears in Dali’s art), since the white negative space implies a face without depicting one. The other reason I love this photograph, though, is that casts Dali in a certain type of light. As an “invisible” figure in this photograph, Dali is a person, but obviously not a “regular” or “normal” person. He is special.

Ever the eccentric, Dali wanted to be seen as someone who was different from regular society. In many ways, I think that his career and personality are an explosive reaction to the “artist-genius” construct which had slowly developed in Western society since the Renaissance. (In fact, speaking of the Renaissance, I think that Dali also viewed himself as a “Renaissance Man,” as evidenced by how he characterizes himself during his appearance on the game show “What’s My Line?” in 1957.) Dali wanted to claim special creative powers and psychological abilities as an artist-genius, which I think ties into Dali’s “paranoiac-critical method” (his term) that he used when creating art.

On a basic level, I think that the paranoiac-critical method can be defined as a way in which Dali cultivated and explored how a paranoid person can “misread, mangle, and misconstrue ordinary appearances.”1 So, as a result of self-induced paranoiac-critical activity, the artist can see things simultaneously, both as rational and irrational objects. In other words, Dali claims that he, as a unique individual, has the special ability to see things as a rational being (an objective artist) and also as a paranoid person. Dali maintained that he was not mad, but could participate in paranoic delirium as both an actor and a spectator.2 Dali’s theory, then, is based off of a willful misreading of Freud, since Dali claimed that he could intentionally embrace both the conscious and unconscious minds.3

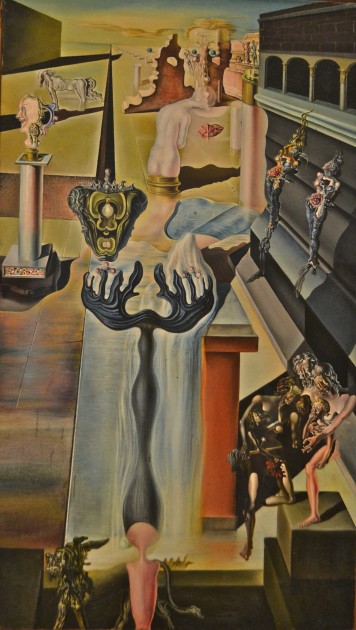

Just like Dali wanted to be seen as fluctuating between the sane and insane, Dali often painted “double-image” works of art (as a result of paranoiac-critical activity) which can simultaneously be “read” in at least two ways. One of the best examples of such double imagery is Metamorphosis of Narcissus (see below). There are lots of things in this painting that can play with the viewer’s eye and mind, but I think that the most common example is that the figure (Narcissus) looking into the water on the left is mirrored on the right by the image of a large hand holding a cracked egg. More double-image details in this painting are discussed in a short video clip by Smarthistory.

Salvador Dali, "Metamorphosis of Narcissus," 1937. 51.1 cm x 78.1 cm (approx 1.67' x 2.5'). Tate Museum, London

The Tate Modern site claims that Metamorphosis of Narcissus (painted 1937) was Dali’s first painting made entirely in accordance with the paranoiac-critical method.4 However, this isn’t the first painting by Dali to incorporate double images. Several years before this painting was made, Dali’s wrote an essay (“L’Âne Pourri” in June 1930) which already mentioned the double image is part of the paranoiac thought process. At the time this essay was written, Dali had begun painting The Invisible Man (see below).5

Salvador Dali, "The Invisible Man," 1929-1933. 140 cm x 81 cm (approx. 4.5' x 2.65'). Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid

Dali began to work on The Invisible Man, therefore, about the same time that he began to establish his ideas about the paranoia-criticism. Dali’s ideas about paranoia-criticism changed and morphed (as did his art) over time, which make his theory difficult to discuss in a nutshell.6 (If you do know of other ways to concisely discuss this method, please share!) But I agree with Haim Finkelstein in that Dali wanted to promote his method in order to gain favor and theoretical legitimacy with the Surrealist group in the 1920s.5 In that sense, Dali didn’t want himself to be seen as an “invisible man” among the more scientifically-engaged Surrealists at the time.

Dali’s relationship with the Surrealist group did not last forever. In a famous trial in 1934, Dali was expelled from the group. In some ways, I think that his paranoiac-critical method was a little too personalized for the other Surrealists. This ego-centric methodology and mentality of an artist-genius must have been confirmed to the other members of the group when Dali said, “I am Surrealism!” in response to his expulsion.

From what I can tell, Dali seems to be the only Surrealist artist who claims to experience a state of paranoiac delirium without any other external aid. His method differs from the artistic methods (such as automatism) employed by other Surrealists, which could involve drug-induced hallucinations or “sleeping-fits” in order to help aid the artist in approximate irrational and unconscious thought.7 Dali, in contrast, famously said, “I have never taken drugs, since I am a drug. I don’t talk about my hallucinations, I evoke them. Take me, I am the drug: take me, I am hallucinogenic!”

Of all the artists who have described or claimed to be an artist-genius, I’m pretty sure that Dali is the only one who has claimed to a drug! You can’t get much more unique than that.

1 Marilyn Stokstad and Michael W. Cothren, Art History, 5th edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Pearson, 2014), 1058.

2 Haim Finkelstein, “Dali’s Paranoia-Criticism or the Exercise of Freedom” in Twentieth Century Literature 21, no. 1, Essays on Surrealism, (Feb. 1975): 64.

3 Dr. Steven Zucker, Smarthistory video, “Metamorphosis of Narcissus”: http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/dali-metamorphosis-of-narcissus.html

4 It is interesting to consider how Dali was proud of Metamorphosis of Narcissus as an example of his method and work. When Dali met Sigmund Freud in 1938, he took this painting with him to show Dr. Freud an example of his method and work.

5 Finkelstein, 62.

6 For a more complete discussion of Dali’s paranoiac-critical method, see Finkelstein article.

7 One such example of how other Surrealists methods differed from Dali is in Max Ernst’s essay “Au-delá de la peinture” (first published 1936). Ernst skeptically differentiates between Dali’s method and Ernst’s own practical process of frottage. Ernst also says that how Dali’s paranoia-criticism is “a pretty term which will probably have some success because of its paradoxical content” but cautions that “inasmuch as the notion of paranoia is employed there in a sense which does not correspond to its medical meaning.” See Finkelstein, 59.