Monday, October 28th, 2013

Raphael, Transfiguration, and Hasan from 3PP

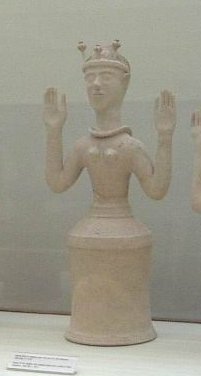

Raphael (with Gulio Romano), "Transfiguration of Christ," 1516-1520. Oil on wood, 405 cm × 278 cm (159 in × 109 in). Vatican Collections

This afternoon I have had a line related to Vasari’s Lives of the Artists go through my head repeatedly. This line comes from part of the biography on the Renaissance artist Raphael, in conjunction with Raphael’s painting The Transfiguration of Christ painting (see above):

“For Giulio Cardinal de’ Medici he painted the Transfiguration of Christ, and brought it to the greatest perfection, working at it continually with his own hand, and it seemed as if he put forth all his strength to show the power of art in the face of Christ; and having finished it, as the last thing he had to do, he laid aside his pencil, death overtaking him.”1

Despite what one may believe in relation to divine callings or destiny, I think we can all agree that Raphael’s early death, at the age of thirty-seven, was premature in relation to his talent and potential. The same should be said of my amazing friend, Hasan Niyazi of Three Pipe Problem, who just passed away unexpectedly. Hasan was passionate about Raphael, and committed himself to creating an open-access database, Open Raphael Online. This project was an enormous undertaking, and Hasan “work[ed] at it continually with his own hand,” much like how Raphael labored with his painting. Raphael did not live to see the completion of The Transfiguration of Christ, similar to how Hasan passed away before his own project was finished. Hasan died when he was barely thirty-eight years old; Raphael died when he was thirty-seven.

I think that theme of this painting is fitting as a tribute for Hasan in many ways, given that “transfigure” means to transform into something that is more beautiful and elevated. In this painting, Christ is transfigured into a beautiful, shining, divine figure, right in front of his apostles. Compositionally, the Transfiguration scene appears above an additional scene in the lower foreground, in which the apostles try to cast devils out of a boy (who medical experts have identified as one coming out of an epileptic seizure).2 In line with the themes of this painting, Hasan strove to elevate his own body and mind into something continually more refined and perfected. He was passionate about learning and had an excellent mind. Hasan was also committed to exercise and running, his work in the health profession, and his stalwart dedication in the art history online community. Although he was not formally trained in art history, Hasan applied his medical and scientific knowledge to learn about and analyze paintings from a technical perspective. He loved beautiful things, and continually sought to fill his mind and eyes with beautiful art, poetry, music, and ideas. He was very intelligent and talented in so many ways.

I am particularly grateful that Hasan sought to connect with art history individuals on a personal level. In many respects, he helped to hold the online art history community together. When I last wrote Hasan an email, I was sitting in an airport, waiting to board an international flight. I had just finished reading a passage on Raphael in Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece, and I wanted to share it with Hasan right away. I quickly typed it into my phone before boarding my plane:

“[Raphael’s] great superiority is due to the instinctive sense which, in him, seems to desire to shatter form. Form is, in his figures, what it is in ourselves, an interpreter for the communication of ideas and sensations, an exhaustless source of poetic inspiration. Every figure is a world in itself, a portrait of which the original appeared in a sublime vision, in a flood of light, pointed to by an inward voice, laid bare by a divine finger which showed what the sources of expression had been in the whole past life of the subject.”3

Like Raphael, Hasan was also a source of inspiration and beautiful ideas. In a way, I think his dedication to digital humanities and accessible information across the globe has parallels with Raphael’s “desire to shatter form.” Hasan’s sincerity, kindness and thoughtfulness were quite unmatched. Unsurprisingly, he made friends all over the world. I feel very lucky to have known him. His death is truly a great loss to all of us.

1 Emma Louise Seeley, Stories of the Italian Artists from Vasari (New York: Scribner and Welford, 1885), p. 171. Available online HERE.

2 Gordon Bendersky, “Remarks on Raphael’s ‘Transfiguration,'” in Source: Notes on the History of Art 14 (no. 4), Summer 1995: 23.

3 Honoré Balzac, The Unknown Masterpiece, 1831. Available online HERE.