Monday, August 26th, 2013

Cats in Ancient Egyptian Art

Detail of cat from the hunting scene (fowling scene) from the tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, Egypt, 18th dynasty, ca. 1400-1350 BCE.

When visiting the British Museum about two weeks ago, I was prompted a few times to think about cats in ancient Egypt. For one thing, I noticed a detail in the fresco fowling scene from the tomb of Nebamun that I had never noticed before. The cat that is included in the scene, whose head is partially damaged, has been given a golden eye by the artist. The text panel near the fresco explained that the although cats were family pets for the Egyptians, in this context the cat “could also represent the Sun-god [Ra or Re] hunting the enemies of light and order. His unusual gilded eye hints at the religious meanings of this scene.”1

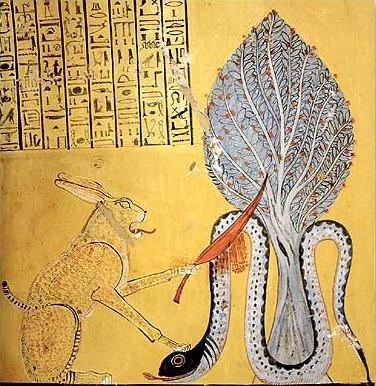

Ra, in the form of a Great Cat, slays the snake-god Apep. Thebes, wall painting from the tomb of Inher-kha, c. 1164-1157. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

It is unsurprising to me that cats could be associated with Ra, the sun-god. In ancient Egypt, domesticated cats were useful for getting rid of vermin, like rats, mice and snakes (especially cobras). Since the sun-god Ra was the greatest enemy of Apep (Apophis), the evil cobra-god of darkness, it makes since to me that cats would be associated with Ra. The wall painting from the tomb of Inher-kha, which shows the sun-god battling Apep, is from the New Kingdom, which is considered to be the time period in which “the cat achieved full apotheosis” in funerary texts and contexts.2 The story of Ra battling Apep is found in the Litany of Ra, which explains how Apep attacked the solar boat as it passed through the sky during the night. Ra overcame Apep, which allowed the sun to continue its journey and be reborn at dawn.

However, Ra was not the only deity associated with cats in ancient Egypt. At the British Museum I also saw the so-called Gayer-Anderson bronze cat on display in another area of the museum. The museum label for the bronze cat explained that this cat was probably associated with the goddess Bastet, the cat-goddess. The British Museum also owns a bronze statuette of the cat-goddess Bastet, although I didn’t find this statue on display during my recent visit. Cats were important to the cult of Bastet, and were bred on an industrial scale by the first millenium BC.

Bronze figure of the cat-headed goddess Bastet, Late Period or Ptolemaic Period, c. 664-30 BC. Image courtesy of the British Museum

Bastet is a mother-goddess with protective and maternal attributes, as shown in the bronze statuette of the cat goddess with four kittens at her feet. Even Bastet’s name, which means “she-of-the-ointment-jar”, suggests a soothing character on part of the goddess.3 Bastet’s associations with ointment also connect her protective qualities to health: she provides protection from contagious diseases. I wonder if ancient Egyptians ever made the association with how their domestic cats fought vermin (that carry disease), which is similar to how the goddess Bastet protected people from contagious diseases.

Detail of sarcophagus of Prince Thutmose’s cat, limestone, sarcophagus height 64 cm, New Kindgom, Dynasty 18, reign of Amenhotep III. Image courtesy Wikipedia via Larazoni.

Due to these associations with gods and their usefulness to Egyptians, domestic cats were treated well. In fact, Egyptian cats were mummified since predynastic times.4 Extensive cat burials have been found at a few sites, including about 300,000 cats at the Temple of Per-Bast, the site of the goddess Bastet. Last summer I remember seeing the small, rectangular sarcophagus of the cat of Prince Thutmose (see above) at a King Tut exhibition.5 The British Museum also has an interesting anthropomorphic coffin of cat. Although some domestic cats may not have had been revered themselves as sacred deities, these pets certainly held a high place of regard within their Egyptian families.6

Do you have a favorite depiction of a cat in ancient Egyptian art? Do you know of other religious or cultural associations for ancient Egyptian cats?

1 Museum label for “Nebamun hunting in the marshes,” London, British Museum, August 13, 2013.

2 Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, The Princeton Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, 2nd ed., s.v. “Cat.” (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008), p. 70.

3 Bastet is seen to be in opposition to the aggressive lioness-headed goddess Sekhmet. See “Bronze figure of the cat-headed goddess Bastet,” from http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aes/b/bronze_figure_of_bastet.aspx. Accessed August 26, 2013.

4 Shaw and Nicholson, p. 70.

5 The sarcophagus of Prince Thutmose’s cat refers to the cat as an Osiris, which indicates that the cat “would be able to reach the netherworld and be judged in the Hall of Truth there.” See Zahi Hawass, Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs (Washington, D.C.: The National Geographic Society, 2008), p. 122.

6 Bob Brier, Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art (New York: William Morrow, 1994), p. 215. Citation found here: http://iweb.tntech.edu/jneapolitan/egypt.html