Sunday, May 26th, 2013

Rublev’s “Holy Trinity”

Some of my friends from high school have chosen very interesting professions and fields of study. A few of these friends studied in divinity school, which can make for interesting conversations via social media. Whenever I have something meaningful to contribute in relation to art, I like to join in the conversation. I thought I’d share some of my thoughts that I contributed to a thread about the Trinity this evening. One of my friends, who is an Orthodox Greek, mentioned that the Hospitality of Abraham is one of the feast days in which the theology of the Trinity is celebrated. He mentioned how the Hospitality of Abraham is popular in icons, and I then popped in with some additional thoughts, which I’ve slightly modified below:

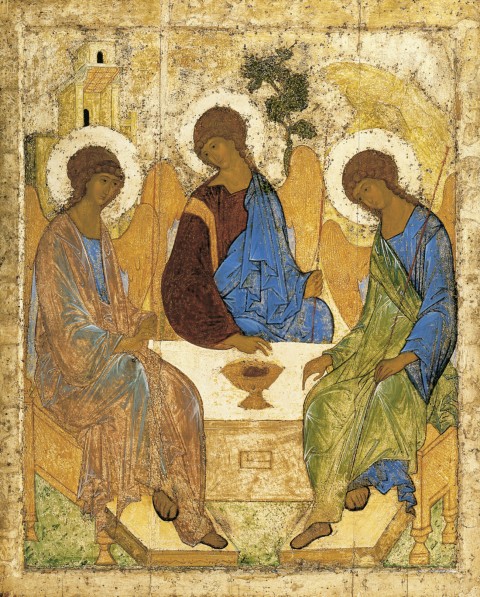

Andrei Rublev, Angels and Mamre (also called "Holy Trinity" or "Three Angels Visiting Abraham"), c. 1410-25. Tempera on wood, 142 cm × 114 cm (56 in × 45 in)

“I think that one of the most famous scenes showing the Hospitality of Abraham/Holy Trinity is the one by Andrei Rublev.

The mountain behind the figure on the right is a symbol for the Holy Spirit (since, for example, mountains are holy locations at which the Spirit can be manifest). The tree (next to the central figure) is a symbol for Christ and the cross. This figure also points to an object that resembles a cup filled with wine. I have read different interpretations regarding the architecture in the background on the right. On one hand, it can serve as a symbol for the house of God, or it can reference the Father as a Creator. Also, obviously, this structure can represent the tent in which Sarah “laughed within herself” upon hearing the prophesy that she would bear a child in old age (Genesis 18:12).

On a side note, I think that the practically identical faces of the angels help to emphasize the unity of the Trinity.”

There are a couple of other symbols and thoughts that I could have added to this comment, but I didn’t want to hijack the thread. I’ll include them here:

- Circular composition of the angels seated at the table emphasizes the eternal and unified nature of the Trinity.

- Each figure wears a blue garment, perhaps symbolizing the heavens.

- I’ve read a couple of interpretations that the seemingly translucent nature of the Father’s garment (the figure on the far left) can emphasize the immaterial nature of God (i.e. the idea of God as Spirit). Although it appears that the quality of the paint may be deteriorating in this example above (which could prompt such a reaction about translucency), we can see that other Orthodox artists who copied Rublev (see an example HERE) also suggest this same idea of a translucent garment.

- The two fingers for the central figure can represent how Christ is both earthly and divine.

- Each figure holds a staff. I think that these staffs serve as symbols of authority and power. Another blogger thinks that the staffs suggest that God walks with men throughout their earthly pilgrimages.

- On a different note, the scale of this piece is larger than you might suppose! It is 142 cm tall (over four and a half feet!).

Does anyone have other thoughts on the symbolism for this icon? On a side note, I think that the sweeping curves and sweet faces of these figures are very appealing. I really like Rublev’s style.