Friday, November 9th, 2012

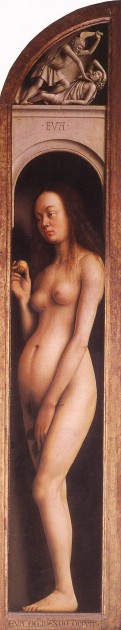

Jan Van Eyck’s “Eve” from the Ghent Altarpiece

How I have missed blogging over the past several weeks! This school quarter is one of the busiest that I have experienced in my career, and I am rarely left with free time to blog or research. I have a lot of ideas for posts swirling in my head, though, so tonight I want to explore at least one topic.

Several weeks ago, near the beginning of the quarter, some of my students of Renaissance art asked some pointed questions about the practice of modeling in Northern Europe. One such question was: “Who posed for the figure of ‘Eve’ when Jan van Eyck painted the Ghent altarpiece?”

I had never considered linking a specific model/individual to that figure, nor had I thought much about the practice of modeling in the Northern Renaissance. I did a little bit of digging and made some inquiries to colleagues, and found some interesting information and theories about this figure.

As far as I can tell from my research, we have no knowledge of the individual that posed for the figure of Eve. I asked my colleague SW (who specializes in Northern art) for her opinion, and she finds it unlikely that Van Eyck (or any Northern artist before Rembrandt) used a nude female model. In her opinion, it seems more likely that Van Eyck built up this female figure by looking at a nude male model (which, if this is true, makes this realistic image even more astonishing and impressive!).

Thanks to an additional side comment from SW, I also have formulated another theory on this topic, too. I wonder if it would have been possible for Jan Van Eyck to have studied a clothed female model, at least in part (perhaps in addition to studying a nude male figure). In her book, Seeing Through Clothes, scholar Anne Hollander has argued that the exaggerated belly of Eve (and other bellies of women that are represented in Northern paintings) can relate to the clothing fashion of the day. While Hollander sees this exaggerated belly as an sign for beauty and refinement (which does make sense to me), I wonder if the exaggeration of the belly also could have been due to practical considerations (i.e. modeling while clothed). There are some similarities, for example, between Eve’s midsection and Giovanni Arnolfini’s wife, the latter being represented in a portrait by van Eyck while wearing fashionable green dress. Could a similarly-clothed woman have posed for the figure of Eve? It doesn’t seem like an impossible idea to me. I haven’t found much information on this topic (or the practice of modeling in Northern Europe) on my own, though. If anyone has ideas or suggestions for future research, please share!

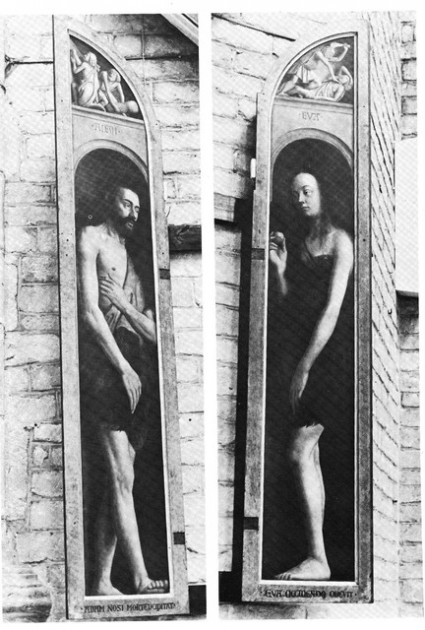

While checking up on this topic, I also was reminded that two copies of the Adam and Eve panels were created in the 19th century, although the figures of Adam and Eve were covered with bearskins in both copies. The copies which were intended for display at St. Bavo’s Cathedral (the original and intended location for the Ghent altarpiece) were created by Victor Lagye in 1865.1 If you consider Hollander’s argument regarding clothing and representations of the female body, in addition to my idea that a model might have posed for van Eyck while clothed, it seems almost ironic that bearskins were added to Eve’s body a few centuries later. In this case, Eve seems to be intrinsically linked to clothing, even without the additional skins.

1 Noah Charney, Stealing the Mystic Lamb: The True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Altarpiece (New York: Public Affairs, 2010), 115.

Nice to see you posting again. Why couldn’t he just have used a female model, either a local prostitute or even his own wife?

However, you’ve made me wonder if Eve appears to be a little bit pregnant. Would this be appropriate for the mother of all the living? Her two sons are depicted above her.

Frank

Hi Frank! Thanks for your comment. Van Eyck may have used a nude female model, which is another possibility. From what I can tell, though, we don’t have a lot of information as to whether prostitutes would model in the North – which is why I think my colleague entertains the idea of a nude male model. We know that prostitutes were used in the South, though, so it isn’t out of the realm of possibility. Van Eyck’s wife may have modeled for the painting, although her face is very different from that of Eve (see Jan Van Eyck’s “Portrait of Margaret Van Eyck”.) If Margaret did model for Eve’s body, another woman could have modeled for the face.

Really, at this point, I don’t think anyone knows who Van Eyck used as a model.

It’s an interesting point about modeling in clothing. I’ll have to check out Hollander’s work.

I’d always believed the interpretation that Eve was meant to look pregnant. Upon reflection though, I really can’t think of any Northern Renaissance depictions of clothed pregnant, let alone naked, women. While a pregnant Eve may make symbolic sense, it would have been a wildly radical image (only compounding the rarity of female nudity for the time).

Thanks for the 1865 images. I’d knew clothing was painted over Adam and Eve but had never seen the image!

Hi M – Im looking closely at the depicted musculature of the shoulders, elbows and knees (using the Hi-Res at the Getty site) and it’s somewhat hard to argue that the artist(s) extrapolated the female from the male – there is a discernible difference in aspects of muscle bulk that is too consistent with observed anatomical nuances.

Until we find a definitive source, we will never know for certain, but do we have any comment on the underdrawing? An extrapolated female form(from the male) would tend to betray this underneath.

In addition, do we know if these sections are attributed to Jan or Hubert?

Many kind regards – always enthralled to have an Eyckian excursion!

H

Hi Hasan! I’m glad that you took the time to look at some of the anatomical nuances. I haven’t come across any comments about underdrawing, but I noticed that you can look at high-res images of Even taken with infrared macrophotography and infrared reflectography of Eve. (There are also x-radiography images available, but I don’t think that the one for Eve is very helpful.) It is interesting to note some changes to the depiction of her right breast, but I don’t know if we can say anything conclusive about that. It seems to me that the head was painted at a different time than the model’s body, though, so that might suggest something. See various images using the drop-down box in the upper left side of this page:

http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/#viewer/id1=25&id2=0

This site is part of the Getty’s ongoing restoration of the Ghent altarpiece. It’s a fantastic site. One can spend many an hour combing through the altarpiece images on there. Perhaps your experience and particular interests will yield some interesting observations.

I’m pretty sure that Jan would have painted Eve, but I don’t think we know for certain. We know that “large layers of paint” were visible when Hubert died, but I don’t think we know the extent of his contribution (beyond that he helped to design the composition in some form).

“Art History Today” just put up a new post: “The Nude in Renaissance Art.” This includes some good information about the history of nudes, as well as some information about models.

I think that I will find more information related to the topic of modeling (at least for male models) by exploring one of the references from this post:

Margaret Walter, The Nude Male: A New Perspective (Penguin, London, 1978).

If anyone has read this book and wants to share their thoughts on it, please comment. I look forward to reading it myself.

I have a question.

What is the Latin inscription on the bottom frame of Eve?