Saturday, July 14th, 2012

The Farnese Hercules and Renaissance “Substitutions”

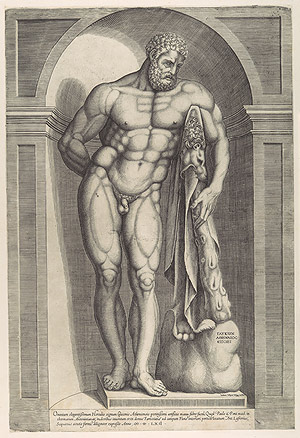

Farnese Hercules (also known as the "Weary Hercules"), 3rd century CE. Roman copy by Glykon after the 4th century BC bronze original by Lysippos. Height approximately 10.4 feet (3.17 meters).

This past week my research meandered into Roman art and the Farnese Hercules. This Roman statue was excavated in various pieces from the Baths of Caracalla during the Renaissance period, in 1546. The legs, however, weren’t found during the early excavations. Before the original legs were discovered, the Renaissance sculptor Guglielmo della Porta provided other legs for the piece. And although the original legs were found not long after, della Porta’s legs were still kept with the statue until 1787, when the originals were finally put into place!1

Apparently, Michelangelo advised that della Porta’s legs be retained with the original statue, in part to prove that modern sculptors could compare with those from antiquity.2 I think this is interesting, given that Michelangelo had already been involved in a longstanding debate with Bandinelli regarding the original composition of the Laocoön. Michelangelo obviously wanted to respect the original composition of classical statues, but it seems like he didn’t necessarily care if the original marble took part in the composition. Perhaps Michelangelo also wanted to promote Guglielmo della Porta, who was his protégé. Anyhow, Michelangelo obviously found that della Porta’s legs were acceptable, although some slight differences can be observed in the position of the feet (see below).

Jocob Bos, Farnese Hercules, 1562. Engraving. Michelangelo designed the niche in which the Farnese Hercules was placed.

After the original legs were finally reunited with the sculpture in 1787, Goethe recorded that he saw the Farnese Hercules in his Italian Journey (1786-1788, German: Italienische Reise). Goethe criticized della Porta’s “substitute” legs, and felt that the installation of the original legs made the sculpture “one of the most perfect works of antiquity.”3

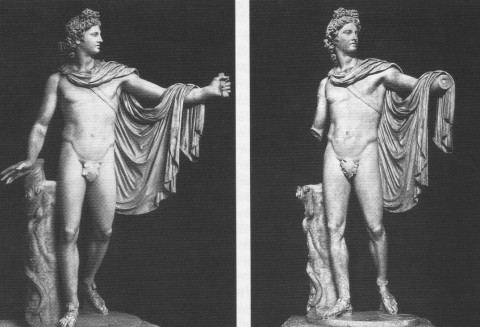

Of course, the Farnese Hercules isn’t the only piece of classical art which was “restored” during the Renaissance period. Although it seems like della Porta’s legs functioned as an adequate substitute for many, I’ll admit that there are other Renaissance “restorations” which seem a bit awkward to me. Perhaps I’m just used to the missing limbs of the “Apollo Belvedere,” but I think that the Renaissance additions on this statue aren’t completely graceful, especially Apollo’s hands and fingers.

Left: "Apollo Belvedere" (2nd century AD) as restored in the 1530s. The left hand, right forearm, and fig leaf were added at the request of Pope Paul IV. Right: "Apollo Belvedere" as restored after WWII. The Renaissance additions were removed, with the exception of the fig leaf. Today, the fig leaf has been removed, but it appears that the Vatican currently displays a restored version of the statue that is similar to the Renaissance restoration. If anyone has information on when this most recent restoration took place, I would love to know!

When considering the post-WWII restoration of the “Apollo Belvedere” (in which the Renaissance additions were removed), Jas Elsner wrote that “whether the modern concern to return such marbles to their ‘authentic’ form constitutes an improvement is, and will remain, a moot point.”4 I’m up for discussion, and I’d like to see what people think about “improvements” and “authenticity.” Do you have any thoughts on the substitutions and “restorations” of Greco-Roman sculpture that took place during the Renaissance? Is it better to only leave original material on these works of art? Should we make conclusions about later “restorations” on a sculpture-to-sculpture basis, depending on the nature and quality of the addition/substitution? (And if so, does that mean that we value aesthetics and our opinion of quality more than original history?)

I feel like these are tough questions for me; I fluctuate between both camps. I am a sucker for original context and original works of art, but I do think that sometimes a substitution can help to recreate the original context in some form. If della Porta didn’t create substitute legs for the Farnese Hercules, the monumental height and overwhelming effect of that sculpture would have been lost (until, of course, the original legs were found). On the other hand, I also think it’s important to realize that the works of art have their own history, even beyond the period in which they were created. Sometimes I like having a visual reminder that specific works of art held importance during the Renaissance.

1 Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500-1900 (New Haven:Yale University Press, 1981), 229.

2 Ibid. See also Jan Todd, “The History of Cardinal Farnese’s ‘Weary Hercules,” in Iron Game History (August 2005): 30. Todd citation can be read HERE.

3 Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey (Penguin Classics, 1970), p. 346. Citation can be read HERE.

4 Jas Elsner, Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 16.

I understand the conflict between the desire to see a work of art as it was originally intended and not wanting to “sully” it with later additions. I tend toward the view that it’s better not to amend the original. Everything on earth is subject to aging in one way or another, nature takes its course, and all things must pass. We must learn to accept change, even embrace it. This all sounds very metaphorical, equating art with life, but as things change our perception also changes. For instance, I think the Venus de Milo is beautiful even with no arms. I don’t think the piece has lost any of its impact because of missing parts – in fact, the grace of the body stands out because the arms are missing. It would look odd to us now to see it with arms added.

I think restorations and such have to be considered on a case-by-case basis. If one institution possesses the whole of an ancient piece, keeping the elements separate seems somewhat silly (and in a case like that of the Farnese Herakles, a cast would be one way to display a removed supplement, if its creator was a significant figure and / or it was thought worth displaying in its own right); if we don’t possess the whole piece, it might be acceptable to leave a supplement in place, provided labels, and especially publications using photographs, are clear about what is what (or one risks arguments being made based on what are mistakenly presumed to be ancient elements).

On reading this post, I was also reminded of one from January 2010 by the Guardian‘s Charlotte Higgins, mentioning the question of whether to retain a more modern restoration by a notable artist (though in that case the argument for retention seems to me much weaker, because what he did seems not to have lasted, so retaining it leaves us neither with a purely ancient object nor with a sight of what he intended).

Thanks for the comments!

Yes, Val, I think that it is important to remember the passage of time when looking at ancient works of art, too. I think that there is something very powerful that is conveyed through broken works of art which have withstood the centuries. Even when there are restorations or additions to an ancient piece, it’s nice if one can spot the difference between the restoration and the original material (so one can at least be somewhat reminded about the passage of time).

Terrence: You’ve implied a great point, because today some works of art are divided among various museums (and countries!). And, of course, many fragments have been lost to the sands of time. I like your suggestion about using photographs and labels to explain what parts of a work of art may have been restored.

The article that you mentioned is very interesting, too! A work of art would embody more meaning if a restoration was completed by a notable artist. I wonder, though, if that new meaning would detract from the original context and purpose of an ancient piece? On the other hand, a notable artist could add some new meaning in relation to today’s history and audience.

Serendipitously, on Monday Mary Beard blogged on two more statues, also from the Farnese collection, where reconstruction and apparent restoration seem to create or exacerbate a whole set of puzzles: those traditionally regarded as Roman versions of the Athenian portrait pair of the tyrannicides Harmodios and Aristogeiton.

I did indeed have in mind cases where a single piece is spread across different museums; for example the archaic Athenian “Rampin Horseman”, whose head was found first and is in the Louvre, while the remains of the torso and mount are in Athens, with each museum displaying its portion with a cast of the rest.

In evaluating the worth of restorations, I think intent (where it is documented) is also important: even if work was done by a notable artist, if the aim was to restore the piece to its ancient state, then there is a stronger argument for treating it like any other museum restoration (and any serious restorer will know that his or her work might be replaced or superceded in light of future findings or techniques). Of course, not all restoration is alike: with a sculpted supplement to a statue, it would be relatively easy to display both the remains of the original and the supplement, without damaging the integrity of either; with that applied to pottery, for example, it might well be a choice between retaining the restoration or alteration, and losing it entirely. The significance of the original work might also be a consideration: if it is of a type that is not rare, and / or it is relatively easy to distinguish or mark the visible layers, then it is more tolerable to keep even a poor or failed restoration (and it might even have a valid place in a museum, as a record of historic treatment), than it would be if the restoration obscured or significantly altered the appearance of what was agreed to be a rare or very significant ancient piece.

Wow, I wasn’t familiar with the Rampin Horseman until I read your comment, Terrence! That’s a really interesting example, since both the Louvre and Acropolis Museums use casts to help display their portion of the statue. I wonder if there are other “divided” works of art that are displayed in similar ways.

I also like your thought about how unrestored works of art can serve as a record for historic treatment. In a way, from a historical perspective, it seems like having both restored and unrestored examples would be useful. The restored examples also can also serve as historical evidence for today’s history (i.e. how we treat and value pieces today). Several hundred years down the road (if humans still value history!), it might be of interest to know what approaches were taken toward historical artifacts in the 21st century.

Thanks for including the link to the Mary Beard post, too. The serendipitous timing of our two posts is quite fun!

An old problem.I

In 1949, age 21, I climbede Acropolis to the Parthenon with the poet Louis MacNeice.

ead of

When he fell and hit something, the tall Irish poet, thenead of British Institute in Athens for 2 years, got u, wiped the blood off my face with a pocket handky and said, “I climb the Acropolis, I fall and my head hits the ground, I bathe my head it si blood and marble>”

The Parthenon was a shadow of what it is now, When the Persians burnt the Acopolis, instaed of restoring it with wood, they used marble. Thjey didn’t dare about authenticity. It was alive and they wished to keep it so, They are still alive. We should tastefully give antiquty back its fullness and beauty. Now one an see the Partheon from much of Athens below, night and day, and it is glorious, Please hush, the unenlighted archeologists or whoever. Let ancient Greece live. Willis Barnstone.

Webstie under name, Most reent books are Poet of the Bible (Nneworton), and a recent new edition with Shambhala Books of my Sappho. Not like earlier ones with facing Greek.

professor willis barnstone IU, USA