Thursday, April 26th, 2012

Watercolor as Underdog

One of the classes I’m teaching this quarter includes a lot of avant-garde art from the 19th and 20th centuries. Last week, a student observed that we haven’t been discussing watercolor paintings as a class. I thought this was a good observation, and responded that avant-garde painters often (but definitely not always) stick with oil and canvas as a medium. This reliance or insistence on oil makes sense for a lot of reasons. On one hand, avant-garde artists seemed to want to “reference” the tradition of oil painting while simultaneously establishing their “difference” from that tradition (to borrow two phrases from Griselda Pollock).

This comment about watercolor, though, has got me thinking. On a whole, I would say that watercolors are not highlighted or discussed very much in general art history textbooks (or in the artistic world at large). In some ways, I think this is a little surprising. Water-based paint has existed since prehistoric and ancient times. Several significant European painters also were interested in watercolor, like Albrecht Dürer (see above).

However, it seems to me that watercolor often has played second fiddle to other mediums, including oil paint. (Maybe it’s part of our human psyche to be reliant on all types of oil – hence the contemporary issues with oil drilling today! Ha!) In fact, in 1804 a group of disgruntled watercolorists banded together in Britain. These artists were upset that watercolor did not receive very high status by the Royal Academy (which had created a hierarchy of artistic mediums). One British watercolorist, William Marshall Craig, even felt compelled to debate the superiority of watercolor over oil painting.1

So, is watercolor really less pervasive of a medium than other types of paint (from a historical standpoint), or does our current view of history simply privilege other mediums? Do we not value watercolor as a medium very much? I haven’t come up with all of the answers (feel free to leave your own opinion), but here are some of the things that I’ve thought about:

- Going back to the Baroque period, watercolor was used by artists for preliminary compositions, cartoons, or copies. (One such example is a kitchen scene by Jacob Jordaens, which happens to fit quite nicely with my recent post on meat and art). Perhaps watercolor has escaped a lot of attention because it is seen in connection with “unfinished” or “lesser” works of art.

- Today art museums do not highlight watercolor as much, due to the fragile, light-sensitive nature of the medium. I remember a curator once telling me that watercolor paintings can only be displayed for a short period of time (six weeks?) before they needed to be taken down or rotated with another painting. Perhaps if watercolor paintings were inherently a little heartier, then they would receive more exposure (ha ha!) to the public eye?

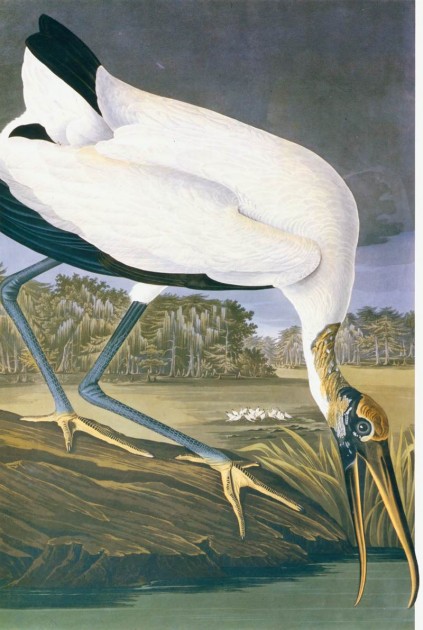

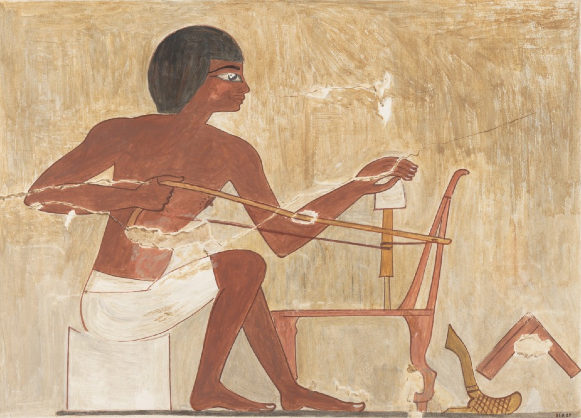

- Watercolor is also associated with things that are not strictly labeled as “fine art” (or, along these lines, “art for art’s sake”). For example, watercolor paintings often appear in naturalist field guides. The connection with watercolor and nature has been longstanding, perhaps reaching its zenith in the work of John James Audubon in the 19th century (see above).2

- Avant-garde artists might have wanted to “reference” the longstanding tradition of oil painting (and perhaps better challenge the Academy by using a medium which was valued at the time?).

I’d love to hear other people’s thoughts on the topic. Do we need to write some revisionist history to include more watercolor painting? What watercolor paintings do you enjoy and/or feel like they deserve more attention? Are there watercolor paintings that you find to be historically significant?

1 William Marshall Craig put forth four arguments in defense of the superiority of watercolor paint. First, he finds that watercolor gets a brighter range of tones than oil paint (partially because the white of the paper produces a brightness that is unattainable in oil). Second, he argues that transparent watercolors allow for clarity and detail that cannot be achieved with oil. (I personally don’t completely agree with that point.) Third, watercolors do not change in appearance when they dry, which is different from oil. Fourth, he finds that watercolor is better for working outdoors, which is necessary with the increasing interest in naturalism. I think this last point is really interesting, especially since he made these arguments several decades before Impressionism. If painters had focused on watercolors a bit more, I wonder if Impressionism (or a similar movement to Impressionism) could have happened several decades earlier. Craig’s arguments are outlined in the book, Great British Watercolors from the Paul Mellon Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 2. Citation available online HERE.

2 Audubon is best known for his “The Birds of America” publication (1827-1838). The complete watercolor work of Audubon can be seen HERE.