Tuesday, January 24th, 2012

The Prude Nude: Censorship and Cover-Ups in Art

For some reason, over the past several days the topic of nudity and censorship keeps popping up in my work (and on Twitter!). I thought I would share some of the interesting things that I am sharing with my students (and have recently discovered).

First off, I suppose I should admit I think that censorship (or cover-ups) of nudity often are a bit amusing. Drapery, fig leaves, conveniently-placed branches – it’s quite an interesting phenomenon in Western art. I often joke with my students about how a bit of drapery conveniently blew across the battle field, right over David’s torso, just before the shepherd boy killed Goliath. (It must be so, right? Bernini recorded the event as such.)

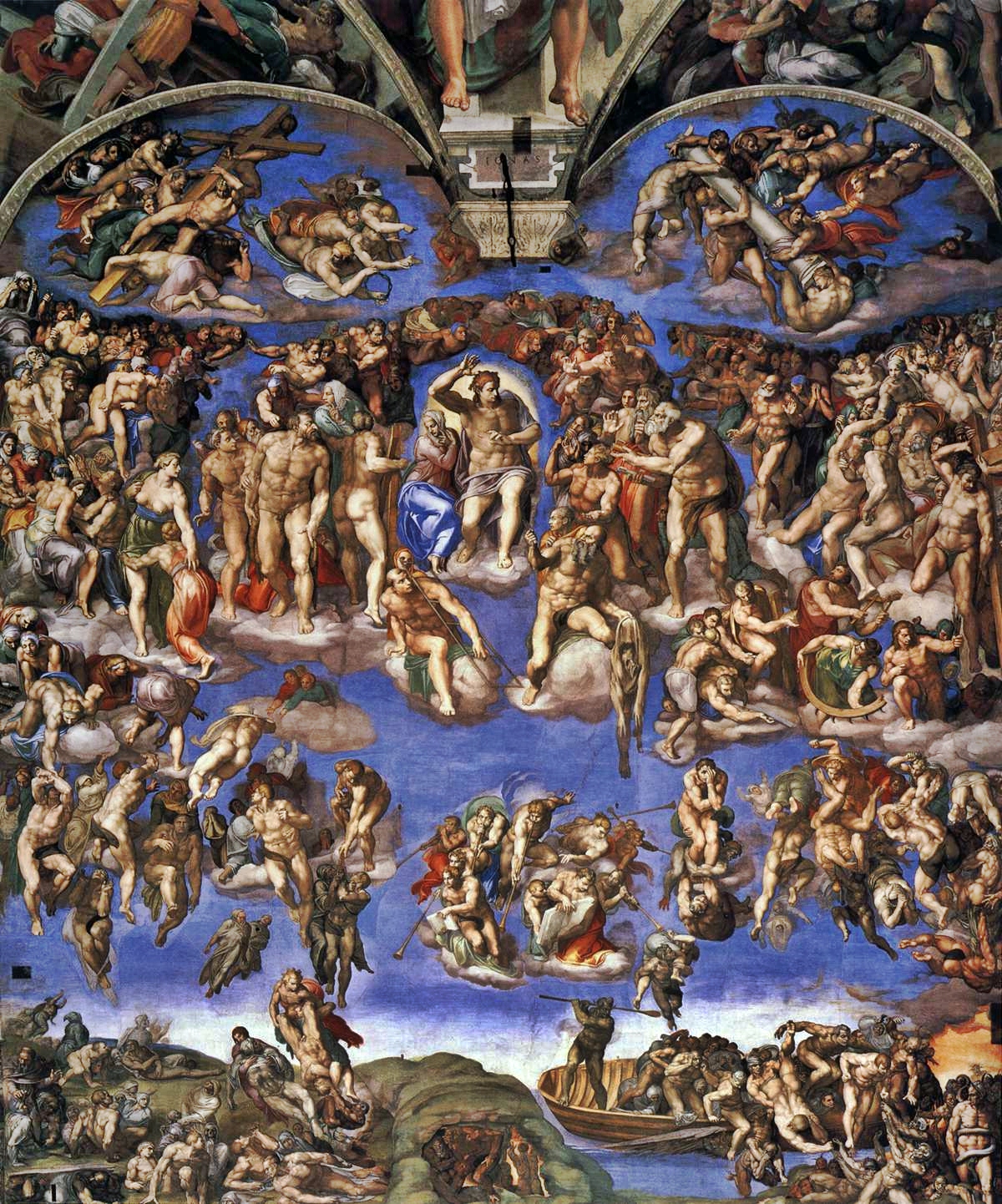

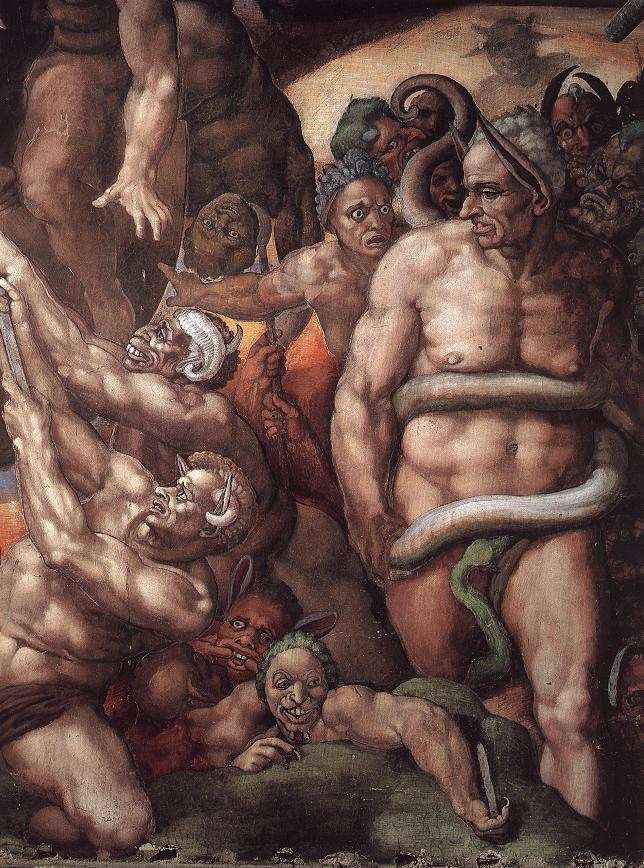

Next week, my students will be learning about Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” fresco from the Sistine Chapel ceiling (shown above). I imagine that this is probably the most well-known story about censorship from the Renaissance period. Right off the bat, discontent was expressed at the nudity shown in the Last Judgment scene. (Side note: I think this complaint is a little strange, because there are plenty of other “Last Judgment” examples in art in which the damned are naked. Perhaps people really had issue with the fact that both the righteous and damned were fully-exposed?) Vasari records that when the Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, saw the almost-finished painting and commented that the nudity made this painting more fit for a bath or a tavern than the pope’s chapel.1 Michelangelo, notwithstanding, decided to paint da Cesena’s portrait on a nude figure (see below). Da Cesana appears in Hell as the figure of Minos. Michelangelo even added some donkey ears, for some extra flair (and humiliation). Luckily (or perhaps unluckily) for da Cesena, Michelangelo covered the man’s genitals with a serpent.

However, the story of the Last Judgment and censorship doesn’t end there. During the meeting Council of Trent in 1563-1564, the indecency of the Last Judgment fresco was a topic of discussion. It was decided to that the painting should be modified so that the genitalia would be covered. (One can only imagine how Michelangelo must have felt if he heard the news; the artist died in February 1564.) Soon after, in 1565, the artist Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint bits of drapery over the nude figures. Unfortunately for Volterra, the commission had a negative effect on his career. Henceforth the artist was known as “Il Braghettone (“breeches painter” or “underclothes painter.”)

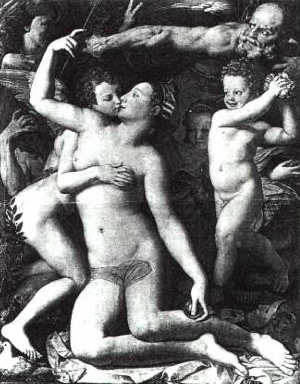

Censorship continued through the centuries. I’m particularly reminded of when Masaccio’s Adam and Eve (“Expulsion from the Garden of Eden”) were covered in the 17th century with little <ss>tutus</ss> vines (which were removed when the fresco was restored in the 1980s). And the austere Victorians also liked to cover up their subjects. I think one of the most interesting examples is Bronzino’s Allegory of Venus and Cupid (c. 1545). In the 19th century, Bronzino’s subjects were “made decent” with the help of a myrtle branch (placed over Cupid-the-Contortionist’s rear) and a clumsily-painted veil over Venus’ torso (see image below). Venus’ left nipple was painted out of Cupid’s grasp, too. Finally, Venus’ tongue was also painted out of the picture, so that her incestuous kiss would Cupid would be a little more, um, chaste. These modifications were removed when the painting was restored to its original state in 1958.

It seems like there must be a demand or interest in the topic of censorship and art. A few days ago, a tweet alerted me to a relatively new program on BBC4, “Fig Leaf: The Biggest Cover Up in History.” You can watch a short introduction to the documentary on YouTube or watch the whole thing online. The film covers the history of the fig leaf in art, explaining when the fig leaf began to be used in Christianity. The show first explains how classical statues were shown in the complete nude, and one scholar explains how the small phalluses shown in Greek statues were seen as a symbol of restraint and control. (I didn’t know that!)

At one point in the documentary, a specialist explains how the fig leaf both covers the genitals but also draws attention to this area of the body (a similar effect, I think, to the Venus pudica pose). I think that’s a very good point. In many respects, one can argue that these “cover-ups” ended up having a reverse effect than what was intended. Even the outcries against nudity just cause people to focus on the naked figures even more.

Okay, now it’s your turn. What are some censored works of art that stand out in your mind? What are your favorite (or not-so-favorite) depictions of fig leaves?

1 Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists (translation by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 461-462.

2 You can read a little bit more about the censorship of the “Allegory of Venus and Cupid” at the short article entitled, ‘A ‘most improper picture.'”