Thursday, September 15th, 2011

New(ish) Romanesque Theories

Boy, art history keeps me on my toes! If I ever start to feel too comfortable in my knowledge of an artistic period, I get knocked off of my feet again by discovering some new theories! Here are two new(ish) theories that I recently have learned about Romanesque art:

Theory #1 – Gislebertus the Count

For those of you who love that Autun Cathedral and the sculptural program there, this fairly new theory by Linda Seidel may come as a surprise. For a long time, it was thought that Gislebertus (and his workshop) were responsible for the sculptures here. This well-founded assumption is based on the inscription, Gislebertus hoc fecit (“Gislebertus made this”) which is located underneath the text of Christ in the Last Judgment tympanum (see above). It sure seems like Gislebertus was the sculptor based on that inscription, right? It was unusual for Romanesque sculptors to sign their work, so Gislebertus has received quite a bit of attention and recognition in the art historical world.

However, Seidel argues that Gislebertus wasn’t a sculptor at all. She finds that he was a late Carolingian count who might have contributed financially to the Autun Cathedral.1 Count Gislebertus made significant contributions to local churches, and his name might have been included in the tympanum in remembrance of his patronage. Seidel even goes further to suggest that this inscription may “challenge those in power to respect and continue the venerable tradition of patronage.”2 For more information, I would recommend Seidel’s book, “Legends in Limestone: Lazarus, Gislebertus, and the Cathedral of Autun” (1999, University of Chicago Press). I haven’t read Seidel’s book myself yet, but I look forward to checking it out. I think this theory is quite compelling.

And regardless of whether Gislebertus is an artist or count, I “heart” him all the same.

Theory #2 – Hildegard as Artist

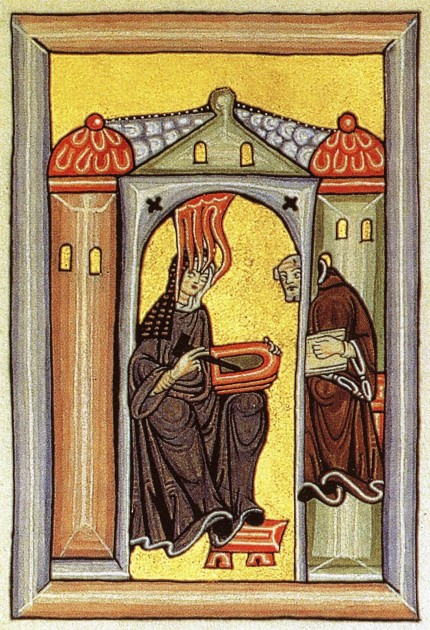

I’ve always remembered when I first learned about the “Hildegard and Volmar” frontispiece of the Liber Scivias (shown above) as a student, since my professor joked that the stylized flames of fire (representing Hildegard’s vision) looked like tentacles. I can’t remember his joke verbatim, but it was something like, “and we can see in this manuscript that the Spirit of the Lord descended on Hildegard like a squid.”

All joking aside, I’m very interested in the new(ish) theory regarding the Liber Scivias. This book is a text that contains descriptions and illustrations of Hildegard of Bingen’s visions. This theory by Madeline Caviness proposes that Hildegard might have been the designer for the illustrations for her visions. Caviness supports her argument in two ways: 1) She finds that these depictions of visions of very unconventional and 2) She thinks these designs also conform to some of the “visionary” aspects that are experienced by people during migraines.3 Hildegard had migraines throughout her life, but especially during the period when she was composing the Scivias.

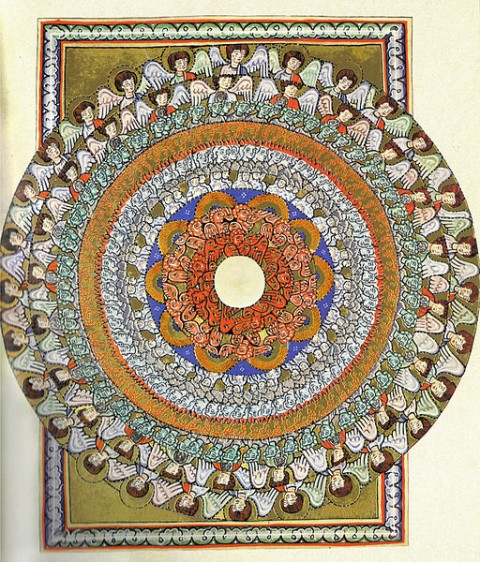

I think this is another interesting argument, and I to think that many of the designs are quite unconventional and unique. One of the images that I like is the “Vision of the Angelic Hierarchy” (1150-1175, shown right). You can see read a synopsis of Hildegard’s visions (and see some small images for some of the designs that may have been created by Hildegard) by looking here.

I hope I can get my hands on a copy of Caviness article; I’d like to learn what “visionary” aspects of these illustrations compare with the effects produced by migraines. More information can be read in Caviness’ article, “Hildegard as the Designer of the Illustrations of her Works” (1998, Warburg Institute).

“Hildegard and Volmar” image courtesy of Wikipedia.

“Vision of the Angelic Hierarchy” image courtesy of Wikipedia.

1 The example of an owner (or patron) signing their name in connection with a work of art has also been seen in later medieval art. An early 14th c manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS selden supra 38) has an inscription which could be interpreted as an indication of the artist, but is certainly the name of a later owner (since it is written in a 15th c hand): “Jehan Raynzford me deit.”

2 Stokstad, Art History (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2011), 478.

3 Ibid., 487.

I agree. The stylised flames of fire, explained as representing Hildegard's vision, may in fact have been something totally different.

Just one example will do. Medieval artists used to depict Moses with horns – a very bizarre image. But in Hebrew, keren can mean either ray or horn. They just mis-translated the word.

My students will be very happy if Gislebertus isn't the artist. That's one less artist's name to remember for slide identifications!

The theory about Gislebertus (love that name almost as much as Theodechilde) being the patron rather than the artist sounds likely. As a precedent, the inscription on the Pantheon in Rome says, "Marcus Agrippa…built it." Of course it means he was the patron, not the contractor.

WTF?!?

/useless comment

Consider my mind blown.

It is always "shocking" when the traditional cannon is questioned but it make logical sense that Gislebertus would/could be a patron rather than artist.

This scenario always begs the question "why hasn't anyone thought of that before?" and that is always fun in Art History.

Thanks for the comments! Hels, I actually didn't mean to imply that the stylized flames/tentacles might be something else other than a fire or vision (I've never considered the possibility of a mistranslation or anything along those lines), but that is an interesting thought!

You might be interested to know that the the most well preserved example of Liber Scivias (thought by many to have been personally prepared by HIldegard) has been lost since WWII. It was moved from Wiesbaden to Dresden for safekeeping and was lost. Some are hopeful that book will resurface one day. The image that I included in this post is actually a colored facsimile of the original manuscript.

LeGrand: Ah, but won't you have your students memorize Gislebertus' name so they can discuss the possibility of him being a count? It's too fun of a name to not memorize!

Val S., I love the name too! I actually had a thought similar to yours regarding inscriptions. I didn't think of the Pantheon and Agrippa (good call!), but I was reminded of Bishop Victor's monograms that decorate some of the capitals in San Vitale. Your example of Agrippa is a much better connection, since they both say that the individual "made/built" something.

alli, YES! I love to blow people's minds! 🙂 I also love that art history is so dynamic. This Gislebertus theory was actually out when you, Josh and I were undergrads. I wonder if MJ and CF have heard of it?

And see Oliver Sack’s text Migraines. He includes illustrations of the ‘scotoma’ and similar art historical speculations. I have this condition myself and can vouch for his accuracy. (Wait! perhaps I’m having visions!)

another similarly speaking object is the alfred jewel, which has essentially the same thing inscribed on it (albeit in old english): AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN. i vaguely recall that there are a number of manuscripts that have a similarly worded colophon, which, of course, gives rise to a number of intriguing ambiguities.

Bob, thanks for the Oliver Sack reference. I’m interested to see the illustrations in his book!

Zillah, that’s really fascinating! The Old English translation says “Alfred ordered me to be made,” right? That slight change in wording from the Gislebertus inscription helps to ensure that there isn’t confusion among historians regarding the patron/artist of the Alfred Jewel.

If there are manuscripts that have a similar phrases, I’d be interested to know whether they differentiate between artist/patron, or if the wording is similar to the Autun Cathedral (i.e. “This person made me”).

Great! But it’s Sacks, not Sack, as I mistakenly said.

best,