Saturday, September 3rd, 2011

Feathers and Colonialism

Over the past few days I’ve been thinking a lot about Amerindian featherwork and colonialism. Probably the best-known examples of featherwork are the “feather paintings” produced by Nahua featherworkers (who were called amanteca). The Aztecs, a branch of the Nahua people, used featherwork for a wide range of prestigious items, including tapestries for their palaces, capes, and head crests.

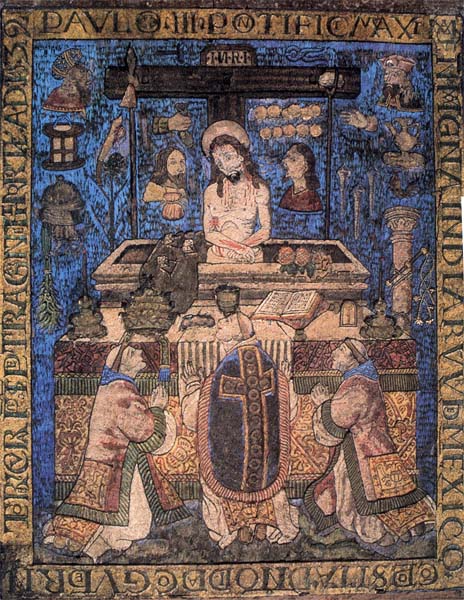

I’m particularly interested in what happened to featherwork after the Europeans came to the Americas. For one thing, Aztec artisans were commissioned to create “feather paintings” in the European style. A Nahua ruler, Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin, commissioned The Mass of Saint Gregory (shown above) as a gift for Pope Paul III.1 From a postcolonial standpoint, it’s interesting to see how the use of European style can be interpreted as an expression of European control. Gauvin Alexander Bailey points out that European “friars wanted to harness this native tradition in the service of Christian propaganda and benefit from the prestige enjoyed by such featherwork in the pre-Hispanic era.”2

Along these lines, Europeans also were fascinated with feather paintings, not only for their technical skill, but apparently for their delicacy.3 I think that this idea of delicacy and fragility is very interesting, given the context of colonialism. With the European mindset of conquering the Amerindians (in terms of politics, culture, and religion), it doesn’t seem surprising that the Europeans would be drawn to imagery that reinforces the delicacy and fragility (in other words, the weakness) of the Amerindians. And I think it is especially interesting that the this idea of fragility is not necessarily embodied in the subject matter for the imagery, but in the artistic medium itself.

Undoubtedly, the feather medium also was a source of exoticism to European viewers. The feathered cloaks of the Tupinambá people (an indigenous group of Brazil) “were collected as objects of curiosity and wonderment by Europeans.”4 No doubt that this sense of wonderment was brought about by the “difference” and “Other-ness” of these objects. Even today, these cloaks continue to instill a sense of awe in European viewers by virtue of their rarity – today only seven such objects remain in European museums. (An image and discussion of the cloak in the Royal Museum of Art and History (Brussels) is found here.)

In fact, the act of collecting featherwork also can be connected to the conquering mindset of Europeans and colonists. One can argue that Europeans were able to “own” or “control” Amerindians through the collection and ownership of feather art. Works of art can be transported, manipulated, bought, contained (think of the Cabinet of Curiosities in the 16th and 17th centuries), and sold – similar to how the Amerindians were treated by various European groups.

1 This feather work copies the composition and details of a 15th century German engraving, Mass of Saint Gregory by Israhel van Meckenem.

2 Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Art of Colonial Latin America (London: Phaidon, 2005), 104.

3 Ibid., 105.

4 Edward J. Sullivan, “Indigenous Cultures,” in Brazil: Body and Soul (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2001), 78.

Image credit: Public domain image via Wikipedia.

Are you aware of this?

Actually, I met one of the people who were/are involved in the project a while ago and, let me tell you, she had some interesting stories to share about the time they all went to Mexico to get the photos taken for the exhibition catalouge…

Hi C! I wasn't aware of this exhibition at all! Thanks for sharing. It's also good to know that an exhibition catalog was produced. I'll see if I can track down a copy. Thanks for the tip!

M:

Excuse me for getting off topic but I thought you might like to know (if you don't already) that the scene depicts Pope Gregory's vision of "the Instruments of the Passion."

Clockwise from the top I can make out the pincers used to remove the nails; the pitcher and basin used by Pilate to wash his hands; the nails; the scourging column and whips; and the Lantern. Judas is in the center with the pieces of silver.

Also, in the California Missions there is much evidence that the musical talents of the natives were also employed.

Frank

Interesting post! I don't know much about feather paintings, but I wonder if the appeal doesn't also have to do with creating order out of chaos, in addition to the exotic aspect. It seems that birds often represent chaos in European literature.

Hi Frank! Thanks for pointing out more details regarding the subject matter. Yes, this mass service is a depiction of Saint Gregory's vision of Christ (and the instruments of the Passion). According to this story, Christ appeared to Saint Gregory when the latter was performing mass. The van Meckenem engraving (which inspired the featherwork) includes even more details and symbols of the Passion in the background (see link in footnote #1). The subject matter of Saint Gregory's vision was a popular theme in art, and I like several examples from the Renaissance period. Here is an example by Durer and here is one by Ysenbrandt.

Also, I am quite interested by what you said regarding musical instruments. I don't know much about musical talents and Amerindians in the California Missions, but I know that music played a key part in Brazil with the Jesuits missionary efforts. After realizing that music, song and dance were central to the native cultures, António Viera imported "masks and rattles" in the mid-17th century to appeal to the natives. Viera especially wanted the natives to realize that Christians were happy, musical people.

heidenkind: What an interesting idea about chaos! I like it! Feather paintings also have been called "feather mosaics" and perhaps the choppy, mosaic-like layout of the feathers could embody chaos (especially in contrast to the illusionism popular during the Renaissance). Great idea.

This is a totally cool post!