Saturday, March 26th, 2011

Mrs. Arnolfini Might Be Dead!

Yes, the title of my post is a bit facetious. Of course Mrs. Arnolfini is dead – Jan van Eyck’s famous Arnolfini Portrait (shown left, 1434) was made several centuries ago. But I’m actually referring to a relatively new argument: in 2003 Margaret L. Koster argued that this double-portrait includes a depiction of Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini’s deceased wife.1 (Koster recognizes though, that this painting might not be of Giovanni Arnolfini at all – there were no less that five Arnolfinis in Bruges at the time who could have commissioned the painting. In 1998 Lorne Campbell picked Giovanni di Nicolao as the probable commissioner for this painting, since Giovanni di Nicolao would have been in Bruges for some time and would have had ample opportunity to meet Jan van Eyck.2)

Anyhow, I think Koster’s argument is fascinating for several reasons. First of all, Koster reveals an archival discovery that Giovanni di Nicolao’s wife, Costanza Trenta, was dead by 1433 (a year before the Arnolfini Portrait was dated!). And from what we know, Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini never remarried.

So, what does this mean? Koster convincingly argues that this portrait is a posthumous representation of Costanza, a way to remember and commemorate Giovanni’s wife. The oath gesture by Arnolfini could reference an wedding oath already taken, perhaps suggesting a renewal of Arnolfini’s wedding vows and devotion to his deceased wife.

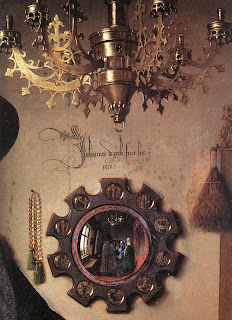

First of all, the idealized depiction of Costanza stands in stark contrast to the very naturalistic and individualized depiction of Giovanni, which could indicate that these two individuals are separated by life and death. Furthermore, there are other aspects in the painting which allude to death. The roundels circulating the mirror frame (see right) are scenes from the Passion of Christ. All of the scenes which show Christ alive are on the left side of the mirror (near Giovanni), whereas all of the scenes alluding to Christ’s death or resurrection are closest to Costanza. Additionally, the lit candle is placed near Giovanni, whereas the snuffed-out candle is placed over Costanza.

The colors of Costanza and Giovanni’s garments could also symbolically allude to their present situation. Costanza is wearing a dress of blue and green: blue was a symbol of faithfulness and green was a symbol of love. Giovanni’s darker clothing can be interpreted as a symbol of mourning or suffering (and Koster further points out that this work was painted before black clothing became fashionable for the Burgundian court).

If you’d like to see Koster explain aspects of her argument, check out the beginning of the “Part 5” section for this documentary. (This documentary on Northern Renaissance art is hosted by Joseph Koerner, another art historian who happens to be Margaret L. Koster’s husband!).

What do people think of this argument by Koster? On a side note, I have to say that I’m always surprised when practicing scholars still refer to this painting as a wedding portrait. That Panofskian approach has been questioned by Northern Renaissance scholars for several decades, and even the National Gallery (which houses this painting) shies away from the wedding interpretation. In fact, I thought the wedding debate was settled in 1993 by Margaret D. Carroll, who pointed out that Mrs. Arnolfini is wearing a headdress traditionally reserved for married women.3 Argh. Despite all of the respect that Panofsky deserves, I really feel like we need to stop interpreting this piece as a wedding portrait. Let’s get on with our lives, folks.

1 Margaret L. Koster, “The Arnolfini Double Portrait: A Simple Solution,” in Apollo (Sept. 2003): 3-14. Text available online here.

2 Lorne Campbell, “Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife,” The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools (London, 1998), 174-204 (see especially p. 195).

3 Margaret D. Carroll, “In the Name of God and Profit: Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait,” Representations 44 (Autumn 1993): 100-101.

I would be perfectly happy to accept that Giovanni di Nicolao's wife was dead by 1433, too early for the Arnolfini Portrait. After all, people loved to remember their beloved family members who had gone to God too early.

But van Eyck would have had to have seen existing sketches or paintings of Mrs Arnolfini, to be able to capture her likeness, well after she had died. Is there any evidence of previous paintings being available?

Maybe Van Eyck saw dead people.

I like Koster's reading too. She is also interviewed in the Januszczak program on this work.

I enjoy the parallels the composition has with Annunciation pictures, and the Lucca/Ince Hall Madonna and child variants by van Eyck(and his workshop). Those, along with the St Margaret Motif in the bed head are great arguments to show that the womam depicted is/was with child (and may have died as a result).

I'd also be interested to know what you think of the Hockney-Falco assertion that a a camera obscura lightsource is depicted in the mirror of the work – but that is a separate topic entirely!

There is a great hi-resolution capture of this work at wiki commons for those who want to take a closer at look at all of its fascinating elements.

Also, an embedded clip from the Januszczak program on this work can be found at this link.

I wish I could access the original Apollo article Koster wrote. I'd like to read her entire argument in context.

Kind Regards

H

I'm not sure that she is dead in the portrait, but I find it a very intersting interpretation.

Interesting theory that seems plausible. Thanks for drawing attention to it.

Since the female is rather idealized I'm not sure Van Eyk would have to have been familiar with her in life.

It is one of my favorite works at the NGL which is saying a lot since it is full of treasures!

I was just looking at an enlargement of this on Wiki. The detail is astonishing.

Not an expert but here are some thoughts. Although I recognize that this is the dress of the time, I've never seen a depiction of a woman, besides the Virgin Mary, (who is supposed to look matronly) with her dress bunched up like that. Do you know of any others?

There's two pairs of discarded shoes here. Like the "Paul is dead" craze, could this signify death?

Also, I believe they're apples not oranges. A piece of fruit on the windowsill is definitely an apple and there is fruit growing outside their Belgian window which are probably not oranges. The apple is a symbol of love and sexuality.

So on the left you have apples, the symbol of love and fertility – on the right you have a marriage bed. In the middle you have Arnolfini's fecund wife. I've always thought that this painting was just a rich merchant showing off his wealth. She may have died before the painting was completed. It would have taken months to do such a work.

All I know for sure is Arnolfini is one homely dude!

Changed my mind, it's a peach tree

This is truly the painting that keeps on giving!

Excuse my ignorance – what does the little dog represent?

Maybe this is the first zombie wedding portrait.

Thanks for the comments, everyone! I especially laughed at the witty comments by AdmGln and heidenkind.

Hels, Koster doesn't mention if there are any previous paintings available, but I think that Judy is right: because Costanza Trenta is idealized, Jan van Eyck may not have needed to see a previous painting.

H Niyazi: Your hi-resolution link didn't work for some reason, but I've included it here for anyone who is interested. The detail is quite amazing!

Your observation about Saint Margaret makes a lot of sense. Great point! I'm not familiar with the camera obscura argument; I'll be sure to look it up!

The Clever Pup: Interesting thoughts! Perhaps the cast-off shoes could signify death – although Koster has usually interpreted the symbols for death on the side of the canvas where Costanza is placed. Still, though, that's an interesting thought. Other scholars have noted that the cast-off shoes could be symbolic of a holy ceremony or setting (which I think could still make sense in this context, since Giovanni is showing a renewal of his wedding vows). (And I also think that the fruit is peaches, not oranges.)

As for the green dress, like you said, many scholars believe that the bunched-up clothing was part of female fashion for the day. I'm not familiar with any other examples of such clothing off the top of my head (a lot of portraits show women sitting down, which isn't helpful if you want to see the dress details!). If I can find one, I'll post a link/image in this comments section.

Margravine Louisa: The dog is such an interesting little addition, I think! Like Koster, I think that the dog is a family pet. However, there is more that can be said. Some scholars have interpreted the dog as a symbol of fidelity, which would further symbolize the fidelity of the couple (and in this context, the devotedness of Giovanni to his late wife, I think).

Koster says something along these lines as well in her article: "Panofsky argued that the dog in the foreground at the lady's feet, 'seen on so many tombs of ladies, was an accepted emblem of marital faith', while Hall and Campbell, in contrast, each found the Arnolfini dog to be devoid of symbolic significance. Yet the dog is surely another link to death imagery. In ancient funerary monuments and medieval tomb effigies, of which the tomb of Margaret of Austria–the owner of the Double portrait–is a characteristic example, such dogs served to express 'the mutual affection of husband and wife in a happy marriage.' A case in point is the Count and Countess of Henneberg Tomb by Peter Vischer. The meaning of the dog may or may not be linked to fidelity–the real point here is that a common type of female tomb effigy in this period includes a full-length portrait of the deceased with a small dog at her feet."

A surprisingly convincing argument! I plan to read the article…

Hi M! Thanks for fixing the wiki commons link. I love that our blogs are getting so many comments these days. A great testimony to the increasing popularity and relevance of art history blogs!

For more info on the Hockney-Falco thesis please watch this segment of the presentation by Professor Falco that was a lecture hosted by the Met.

It actually is worth watching the whole series of vids, but this one refers to van Eyck specifically

Beyond Falco's claims and Hockney's visual recreations, there is a solid foundation of optical mathematics that is reproducible across different works and artists.

Any art historian who wants to try their hand at refuting it will need to devise a way fo explaining how their (unscientific) opinion overrides consistent mathematical proofs demonstrated by optical analysis of the works. These detailed numbers are available at Falco's site for those interested.

Here is the link to the Met presentation:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NV2rMGORuaY

Kind Regards

H

Hasan, I apologize for taking so long to reply to your comment. Wow, thanks so much for including the link! I look forward to watching the rest of the series. As you said, the argument is very compelling! You're right: it's hard to argue against mathematical proofs and optical analysis.