Friday, November 9th, 2012

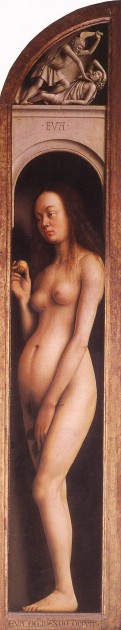

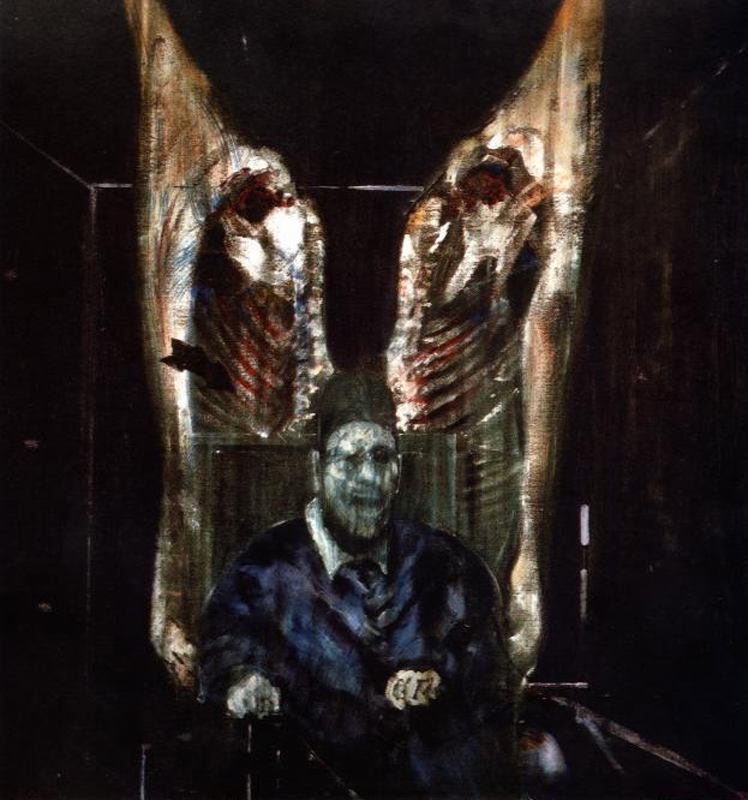

Jan Van Eyck’s “Eve” from the Ghent Altarpiece

How I have missed blogging over the past several weeks! This school quarter is one of the busiest that I have experienced in my career, and I am rarely left with free time to blog or research. I have a lot of ideas for posts swirling in my head, though, so tonight I want to explore at least one topic.

Several weeks ago, near the beginning of the quarter, some of my students of Renaissance art asked some pointed questions about the practice of modeling in Northern Europe. One such question was: “Who posed for the figure of ‘Eve’ when Jan van Eyck painted the Ghent altarpiece?”

I had never considered linking a specific model/individual to that figure, nor had I thought much about the practice of modeling in the Northern Renaissance. I did a little bit of digging and made some inquiries to colleagues, and found some interesting information and theories about this figure.

As far as I can tell from my research, we have no knowledge of the individual that posed for the figure of Eve. I asked my colleague SW (who specializes in Northern art) for her opinion, and she finds it unlikely that Van Eyck (or any Northern artist before Rembrandt) used a nude female model. In her opinion, it seems more likely that Van Eyck built up this female figure by looking at a nude male model (which, if this is true, makes this realistic image even more astonishing and impressive!).

Thanks to an additional side comment from SW, I also have formulated another theory on this topic, too. I wonder if it would have been possible for Jan Van Eyck to have studied a clothed female model, at least in part (perhaps in addition to studying a nude male figure). In her book, Seeing Through Clothes, scholar Anne Hollander has argued that the exaggerated belly of Eve (and other bellies of women that are represented in Northern paintings) can relate to the clothing fashion of the day. While Hollander sees this exaggerated belly as an sign for beauty and refinement (which does make sense to me), I wonder if the exaggeration of the belly also could have been due to practical considerations (i.e. modeling while clothed). There are some similarities, for example, between Eve’s midsection and Giovanni Arnolfini’s wife, the latter being represented in a portrait by van Eyck while wearing fashionable green dress. Could a similarly-clothed woman have posed for the figure of Eve? It doesn’t seem like an impossible idea to me. I haven’t found much information on this topic (or the practice of modeling in Northern Europe) on my own, though. If anyone has ideas or suggestions for future research, please share!

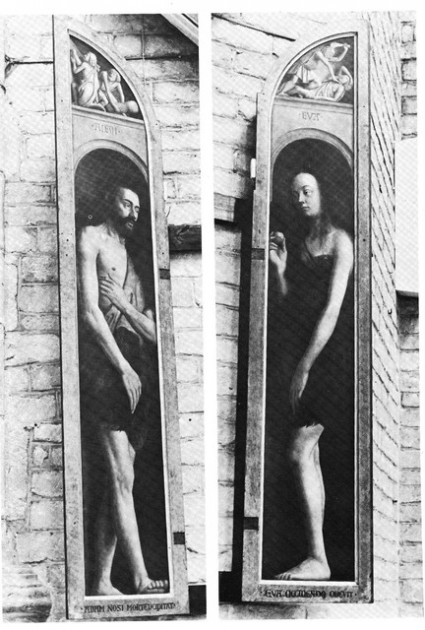

While checking up on this topic, I also was reminded that two copies of the Adam and Eve panels were created in the 19th century, although the figures of Adam and Eve were covered with bearskins in both copies. The copies which were intended for display at St. Bavo’s Cathedral (the original and intended location for the Ghent altarpiece) were created by Victor Lagye in 1865.1 If you consider Hollander’s argument regarding clothing and representations of the female body, in addition to my idea that a model might have posed for van Eyck while clothed, it seems almost ironic that bearskins were added to Eve’s body a few centuries later. In this case, Eve seems to be intrinsically linked to clothing, even without the additional skins.

1 Noah Charney, Stealing the Mystic Lamb: The True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Altarpiece (New York: Public Affairs, 2010), 115.