Wednesday, August 27th, 2014

Roman Imperial Cult Statues

Lately I’ve been doing some research on cult statues of Roman emperors, in order to get a sense of the imperial cult and the imagery that was used within the cult. My initial interest in the imperial cult was prompted by seeing the posthumous portrait head of the Emperor Claudius at the Seattle Art Museum. The museum label and website explain that this sculpture probably was made soon after Claudius’s reign (instead, during the reign of Nero) and probably was part of an oversize, full-bodied cult statue for the then-deified Claudius:1

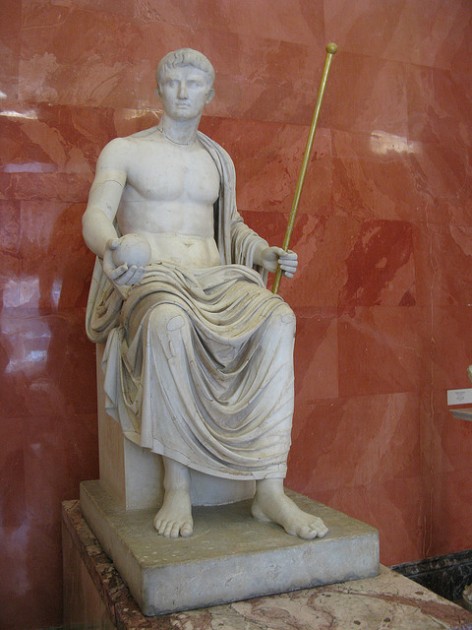

The imperial cult is somewhat similar to a religious cult, but it not wholly religious in nature. Instead, the imperial cult also served the political function of creating solidarity and uniformity across the Roman Empire, despite cultural or language barriers.2 In order to learn what constituted an imperial cult statue, from a visual perspective, I read portions of Polly Weddle’s doctoral thesis, “Touching the Gods: Physical Interaction with Cult Statues in the Roman World.” One of the main things that I discovered was that cult statues could appear in a variety of visual styles, so style is not an signifier to indicate an imperial cult statue.3 This makes sense to me, since Roman emperors employed various artistic styles throughout the Roman era. If the portrait head of Claudius was a cult statue, one can see how this more-so veristic portrait is quite different from the idealized cult statue of Augustus as Jupiter that is in the Hermitage:

Statue of the Emperor Octavian Augustus as Jupiter, 1st quarter of the first century CE. Height 185 cm. State Hermitage Museum. Image via thisisbossi on Flickr (used via Creative Commons License; no changes made).

In addition to style, I have learned that context is very important in determining whether a statue is supposed to receive cult. In addition to cult statues, honorific (but non-idol) statues called andriantes (or sometimes andrias) by ancient writers could be placed in temples as well.4 As a result, it seems like one must rely heavily on ancient writings descriptions in order to determine the cult nature of an object. The physical placement of such objects (within the cella) could also help indicate a cult function.

In Weddle’s paper, she explains that the practice and worship of imperial images tends to be modeled after the worship of “old” or traditional gods in the Roman pantheon.5 However, it appears that, for the most part, deified emperors were not placed on fully equal terms with the great Olympian gods.6 This difference between emperors and Olympian gods may explain why some aspects of cult sacrifice appear to the different. The ancient vocabulary used to describe such sacrificial rituals seems to suggest that the sacrifices are performed on behalf of the emperor, rather than to him.7 However, there are instances of sacrifices being made explicitly to imperial images.8 We know from ancient writings that that people made offerings were made to the statues of the emperors, in order to induce goodwill.9

From what I can tell, it is hard to identify a lot of intact cult statues of emperors today. The practice of replacing the heads of old statues of emperors with new heads may have been relatively common.10 Another issue may have been the combination of mixed mediums for statues, which seems to be the case with the cult statue of Domition (possibly Titus) at the Archaeological Museum in Ephesus (Selçuk):

olossal Statue Head of Domition (or Titus), 1st century CE. Archaeological Museum of Ephesus (Selçuk).

On a side note, it is also interesting to note how other deified people can enter the imperial cult – not just emperors. One such example is Antinous, the lover of Hadrian who drowned in the Nile and was subsequently deified. A colossal statue of Antinous was created for acrolithic cult worship; the extant head for the Antinous Mondragone is in the Louvre collection:

Antinous Mondragone, c. 130 CE. 95 cm (31 inches) height. Louvre. Image courtesy Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikipedia

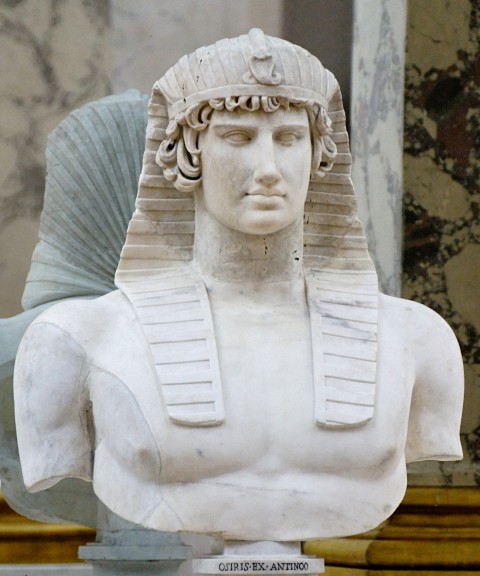

Another great example is a representation of Antinous as Osiris from the Louvre (read more information on the syncretic relationship of these figures HERE). I’m not sure if this statue functioned specifically as a cult statue, but it definitely was associated with the cult:

Antinous as Osiris, c. 130 CE. Originally from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, Louvre Museum. Courtesy Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikipedia

Do you have a favorite cult statue of an emperor? What else do you know about the way that Roman emperors were represented in cult statues? Do you know anything else about the placement and function of such statues?

For further reading:

Takashi Fujii, Imperial Cult and Imperial Representation in Roman Cyprus (see reviews HERE and HERE)

S. R. F. Price, Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor

1 Museum label for “Posthumous Portrait Head of the Emperor Claudius,” Seattle, WA, Seattle Art Museum. August 9, 2014.

2 Museum label for “Emperor Cults and Temples at Ephesus” Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Ephesus, Turkey. June 2012.

3 Polly Weddle, Touching the Gods: Physical Interaction with Cult Statues in the Roman World, PhD thesis, Durham University, 2010, p. 13. In Durham e-Theses, accessed August 18, 2014, http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/555/

4 Duncan Fishwick, “The Statue of Julius Caesar in the Pantheon,” in Latomus T. 51, Fasc. 2 (AVRIL-JUIN 1992): 332.

5 Ibid., 45.

6 Fishwick, 331.

7 Weddle, 224.

8 Ibid., 225.

9 Ibid., 67.

10 Ibid., 184.