Thursday, September 19th, 2013

History of the Halo in Art

Last year, in two different classes, I had students ask me about the history of the halo in art. It is an interesting topic to consider, especially since there isn’t a reference to Jesus having a halo in the Bible. I think that the closest reference to a halo in the Bible is a description of Moses being surrounded with a “crown of light” or “rays of light” (from when he came down off of Mt. Sinai, as recorded in Exodus 34:29). Interestingly, St. Jerome’s Vulgate had a translation of this verse as “horns of light,” and you sometimes see depictions of Moses with horns from the Middle Ages and onward. But that’s another story for another post, perhaps.

I thought I’d write down a bit about the early sources for the halo, in case I have more students ask the same question in the future. The halo may have come from several different sources, including classical culture. For example, the Greek god Helios is depicted with rays emanating from his head (see image above). There also are a few depictions of Apollo with halos. A Roman floor mosaic in Tunisia which has one such depiction. I’ve also heard discussions about how laurel wreaths (used to crown victors in classical societies) could be related to the halo.

In addition to classical sources, the sun disk found in Egyptian crowns may have been an early manifestation of a halo-like form. There also are similar forms related to the halo (like the nimbus or aureola) found in non-Western art, too. Some think that the halo form traveled from West to East, ending up in Ghandara and influencing depictions of the Buddha (see one example from the Tokyo National Museum from the 1st-2nd centuries CE).1

Detail of vault mosaic in the Mausoleum M (Mausoleum of the Julii), from the necropolis under St. Peter’s Basilica. Mid-3rd century CE. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Christians adopted the round halo from their contemporaries, using the circular shape to connote perfection, divinity, and holiness. I know of one early image, a ceiling mosaic from the necropolis underneath St. Peter’s (see above), which may depict Christ or Sol Invictus (the later sun god of the Roman empire). This image pre-dates the 4th century, and could be a very early example of the halo in a Christian context. After this point, halos were used for Christ and the Lamb of God, angels, the Virgin, and eventually saints.2

Some variants of the halo:

- The mandorla (an almond-shaped aureole) usually is used for depictions of Christ and the Virgin. However, the earliest representation of a mandorla appears around an Old Testament figure, specifically one of the three angels who visit Abraham (in a 5th century scene at Santa Maria Maggiore).3 The mandorla continues to become more abstract and angularly defined in later art.

- The cruciform halo is usually used for members the Trinity, especially Christ. This form of halo includes a cross within or extending beyond the circular area of the halo. An early example of the cruciform halo is found in the Miracles of the Loaves and Fishes mosaic of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (c. 504). In Orthodox and Byzantine tradition, the cruciform also include the letters Ο ὤ Ν, which translate to mean “The Being” or “I Am,” serving as a testament to Christ’s divinity (see more information HERE).

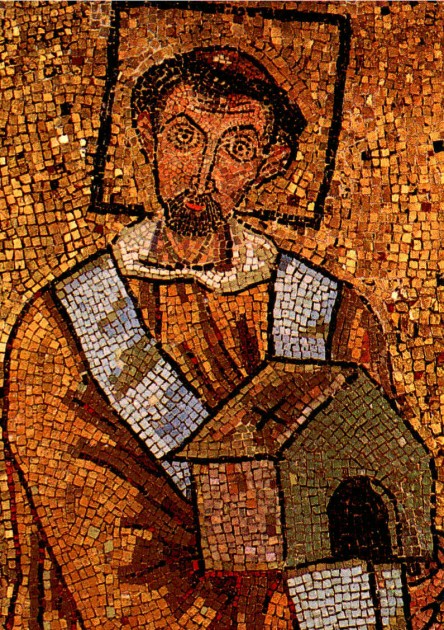

- The square halo was sometimes used to indicate that a person is still living when the work of art is created. From what I can tell, the earliest example of a square halo dates from about the early 8th century. The square, as an imperfect shape that represents the Earth, is used to draw a contrast with the perfect circle used for divine figures. (For an example, see mosaic of Pope John VII at the beginning of this post. Other examples of square halos are found at Santa Prassede in Rome, found in a mosaic of Pope Paschal I (c. 820) and a mosaic which includes a woman specified as “Theodora, Bishop”).

- The trianglular halo is sometimes used to symbolize the Trinity (example: Antoniazzo Romano, detail of God the Father, from the Altarpiece of the Confraternity of the Annunciation, c. 1489-90, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome).

- The hexagonal halo has been used in conjunction with allegorical figures (example: Alesso di Andrea, Hope, 1347. Pistoia Cathedral, Pistoia).

- Dotted halos sometimes appear in Crusader art; they are considered one of the stylistic characteristics of this type of art (example: Saint Sergios with Female Donor icon, c. 1250s).4 The dotted halo also appears in other artistic traditions, too, including Ottonian art (example: Christ and the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee from the Hitda Codex, c. 1025-50).

- The star halo sometimes appears in depictions of the Immaculate Conception. This type of halo refers to the to the description of the Virgin being crowned with twelve stars (Revelation 12:1). Several depictions of the Immaculate Conception appear in Counter-Reformation art, including Velasquez’s The Immaculate Conception c. 1619 and Francesco Pacheco’s Immaculate Conception with Miguel Cid, c. 1621 (Seville Cathedral).

With the rise of realism in Renaissance art, the halo began to decrease (in terms of size and frequency of use). Giotto seems to have struggled with how to depict groups of figures with halos, while still giving a sense of three dimensional space, as seen in his Madonna and Child altarpiece. Masaccio tried to angle his halos to appear a little more realistic in three-dimensional space, as seen in his “Tribute Money” fresco in the Brancacci Chapel. Leonardo da Vinci only subly suggests a thin halo in many of his paintings, like Virgin of the Rocks at the National Gallery in London. In some Renaissance art, sometimes the halo was subtly incorporated into a scene, like the a firescreen (Follower of Robert Campin, Virgin and Child Before a Firescreen) or an architectural device (Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper). I like how Jan Van Eyck created thrones in the Ghent altarpiece with backs that give the suggestion of halos (see above). Beyond the Renaissance, some artists continued to suggest halos without creating a traditional halo, as seen in the drapery behind Christ in Coypel’s The Resurrection of Christ (1700).

What are your favorite depictions of halos? Why?

1 Sally Fisher, The Square Halo and Other Mysteries of Western Art: Images and the Stories that Inspired Them (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995), 92.

2 Ibid.

3 “Mandorla,” Encyclopedia Brittanica. Available online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/361739/mandorla (accessed September 19, 2013).

4 Angeliki Lymberopoulou, “To the Holy Land and Back Again: The Art of the Crusades,” in Art and Visual Culture 1100-1600: Medieval to Renaissance, edited by Kim W. Woods (London: Tate Publishing, 2012), 134.

My favorite halos are the ones in Giotto’s Last Supper because they look like plates stuck to the apostles’ heads.

Yes! I love those halos! I had forgotten about how interesting those halos are, because a few of them look like they are stuck to the faces of the apostles. This is an image of Giotto’s “Last Supper” (from the Scrovengi Chapel), for any readers who are following:

http://www.wga.hu/art/g/giotto/padova/3christ/scenes_3/chris13.jpg

These halos are also interesting because they appear to be black. However, I read here that originally silver leaf was placed on these halos. The silver became tarnished over time, which accounts for the darker color:

http://books.google.com/books?id=s3AjcoLfYMsC&lpg=PA16&ots=00ehHYCj-K&dq=giotto%20silver%20%22last%20supper%22%20halos&pg=PA16#v=onepage&q=giotto%20silver%20%22last%20supper%22%20halos&f=false

M:

The Halo or Nimbus was primarily used to signify the holiness within. I believe it was also used to identify the characters. In that respect Jesus is uniquely shown with a cruciform halo, one that contains the ends of the Cross.Renaissance artists obviously believed that their skill allowed them to depict the holiness in a more naturalistic way.

A good assignment for your students would be to analyze Giotto’s use of the halo in the Scrovegni chapel. Without the halo it would be difficult to pick out Joseph from the other suitors for the hand of Mary. In other frescoes, some participants qualify for the halo while others don’t. The shepherds don’t qualify but the wise men do. Lazarus has one but Martha and Mary don’t. The halo of Judas seems to be fading at the Last Supper but gone at the scene of the betrayal in the garden.

Frank

Thank you for this post, Monica! I am very interested in Caravaggio’s use of halos in art (I mention it in this post and plan to expand on the topic), and your article has given me a wonderful starting point for learning about the history of halos!

Hi Frank! Thanks for this comment! I agree that the Scrovegni chapel paintings by Giotto are fertile ground for the study of the halo. Likewise, I think it is interesting that the “Lamentation” scene includes figures with and without halos, which helps to guide the eye to certain key figures. For those who are reading and following along, this is an image of Giotto’s Lamentation:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/Giotto_-_Scrovegni_-_-36-_-_Lamentation_%28The_Mourning_of_Christ%29.jpg

Thanks for your comment about the cruciform halo! I meant to include that in this post, so I have edited it accordingly.

Hi Amy! Thanks for your comment! I actually was thinking about Caravaggio’s delicate halos after I wrote this post! Despite the grittiness and darkness of Caravaggio’s paintings, his almost-imperceptible halos often add an element of delicacy and spirituality that helps to make his naturalistic subjects seem divine. The halos almost seem like visual buffers for the dirty fingernails, wrinkles, drowned prostitute, etc.

I’m also curious as to whether the halos in Caravaggio’s paintings ever were stipulated by patrons. (It would make sense that halos would be preferred in some ways, given the aims of the Counter-Reformation.) For example, the rejected version of “Saint Matthew and the Angel” for the Contarelli Chapel in S. Luigi dei Francesi didn’t include a halo, but the final version does have a halo. I wonder if the lack of a halo (among other things, undoubtedly) could have led to the rejection of the first painting:

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_CijcaA9yq58/TEZDo4Zvq_I/AAAAAAAAGaA/Fhbj2q1PpF0/s400/destroyed+Matthew.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f8/The_Inspiration_of_Saint_Matthew_by_Caravaggio.jpg

I’d love to know more when you expand on this topic. If you ever want to collaborate on a Caravaggio-and-halos project, I’d be up for it!

The “rules” for haloes developed over a long period of time. For example, the mosaics of Justinian I and Theodora at San Vitale in Ravenna, depict both rulers (living at the time the works were made) with circular haloes.

Hi Laura! Yes, that’s a good observation! The earliest example of a square halo of which I am aware dates from the early 8th century (it is the first image in the post, depicting Pope John VII). Perhaps the rules for the square halo developed sometime between the Justinian mosaics (which date from about the mid 6th century) and the early 8th century. I haven’t seen much scholarly information on the square halo, so I would appreciate if any other readers have ideas or observations on this topic!

I love your ‘visual buffers’ comment – you’re absolutely right. My favorite thing about his halos is when they’re mixed with religious figures in contemporary clothing, because it adds this level of reality and immediacy within the viewer’s own space, as if the figures have just appeared out of Rome’s dusty streets… I’m totally up for working on a project on this with you!:)

I’ve wondered in the past about the symbolism of the Halo on the Christ Child in Masaccio’s

The Virgin and Child. His is uniquely depicted as a solid object in 3 dimension space, while Mary’s and the Angels’ are flat and more abstract. Would this symbolise Christ as being uniquely capable of simultaneously inhabiting a divine (halo) and earthly (with perspective) realm?

Hi Glennis! Thank you for your comment! I really like your idea about the three-dimensional halo on the Christ Child’s head having symbolic content, due to the solidity and “earthliness” of the object. I don’t believe I haven’t seen a halo like that in any other of Masaccio’s paintings. It would be fun to research and see if more of these halos exist, especially from the Renaissance. I wonder if Renaissance humanism would promote an emphasis on the “earthly” aspect of Christ.

I would like to know the significance of what I call “halo hangers” depicted in certain paintings. I’ve always wondered if they were supposed to depict something functional or something symbolic.

They appear to have started out as thick hair ribbons but eventually seem to have become more substantial. I tried to locate some of the paintings I recall seeing them depicted in. They appear to be restricted to the angels , the “chorus”, if you will. I know I recall being struck by them after seeing some paintings in the Uffizi and in the Louvre. They seem to have been a Mediaeval Italian thing.

These are some examples of the stylized ribbon. I forgot to copy the name of the one which appears to be more like a hair ribbon or scarf-like. If I can find more examples of the various styles. I will post the names.

Cimabue: Santa Trinita Maestà

Cimabue: Mary & Angels

Duccio: Madonna & Child Enthroned with Angels & Saints

Hi Anneke! Thanks for your comment. I have never noticed these ribbons before! Their composition is rather curious, since they stick out into space in an angular way; I wonder if the shapes are supposed to evoke some type of letter or object. If you learn more about these, please keep me updated!

Monica and Anneke:

I looked at the angel ribbons that Anneke pointed out in Cimabue’s Santa Trinita Maesta. Rather than part of the halo, I believe they are part of the hair ribbon of the angels. They seem to be continuous with the band that keeps the angelic hair in place, and the loose ends appear to be blowing in the wind. they are not part of the halo.

Frank

Hi Frank. Thanks for your comment. I agree that these are hair ribbons within the halo. I am curious, though, as to how the hair ribbons are stylized. They are curve up and then even out to be horizontally-oriented across the width of the halo, as though they were intended to be visible to the viewer. In a way, this reminds me of the letters that sometimes appear in Christ’s halo in the Orthodox and Byzantine tradition. I wonder if these ribbons have any other type of symbolic significance. Or, as you suggested, perhaps they are supposed to be blowing in the wind to signify the movement of these winged creatures? Either way, it is interesting to see how these ribbons are visually emphasized through the use of the halo. Without the gold background provided by the halo, these ribbons would be difficult to see.

organization of lines, shapes, colors, and other art elements in a work of art. More often applied to two-dimensional art; the broader term is design.

Thank you so much for writing this post! I spent a lot of time in museums over the past month, and I’ve become fascinated by halos. They’re already interesting, conceptually, being physical manifestations of metaphysical grace, but the variety and evolution of their depiction make them doubly interesting. What would you recommend for further reading (e.g. treatises, articles, etc.)?

My favourite halo is <a href="https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/bellini-gentile/annunciation" title="Bellini Gentile's Annunciation“>.

Oops, the HTML didn’t cooperate in that last comment. Here’s the link on its own: https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/bellini-gentile/annunciation

Hi

I enjoyed the article. I keep thinking about auras. There must be some connection between the idea of an aura and haloes. Thoughts? Thanks

In Christian art it is also interesting to see how different halos are used within a single image to represent a kind of hierarchy of holiness. Often the apostles for example have halos of simple gold discs while Christ will have a cruciform halo. The other fascinating variant in halos is found in Islamic art where the holy figures’ heads are surrounded by a ring of fire. Sometimes this fire surrounds their entire body.

The historical background of the appearance of the halo goes back to the Persian civilizations and is seen for the first time above “Mitra”s head.And this is much earlier than the Christianity. It is strange that this point is not mentioned in this article at all.